"There are no heavy weights or light weights, only fast weights or slow weights." – Louie Simmons

Any strength coach worth their salt believes in mastery of the basics over flashy gimmicks and variety for variety’s sake. Keeping in mind that we should always strive to keep our training simple and efficient, Velocity Based Training (VBT) simply provides us a method to do simple better. The world of Performance Coaching seems to have reached a bit of a dichotomy. In the growing age of technology, it seems like some coaches want to be stripped of any decision-making responsibilities and rely on machines to coach for them, while others want to keep technology OUT of the weight room at all costs! As with anything, the best answer likely lies somewhere in the middle. In our private sector setting, we’ve implemented VBT over the last several months with great success, training a variety of athletes ranging from high school to professional to achieve a variety of goals and adaptations. I’m here to explain to you how implementing Velocity Based Training (VBT) can only enhance your current training process and why it’s here to stay!

Before we proceed, we must discuss a few important caveats. VBT is only useful and relevant when intent is high and exercise technique is flawless. A lift performed with submaximal weights and poor effort for the sake of hitting a specific velocity zone will of course yield no positive benefit or adaptation, in the same way that a lift performed with poor technique in order to hit a certain velocity zone will lead to maladaptation or worse, injury. While it is fun to use and can provide extremely valuable insight throughout the training process, we must always remember that as Wil Fleming says, the VBT device is just another coach in the room; it cannot become THE coach in the room. Additionally, we typically like to keep the VBT usage for big compound lifts only, looking at average velocity for your classic lifts (bench, squat, deadlift, overhead press etc.) and peak velocity for the Olympic lifts. Feel free to measure the speed of your barbell bicep curl if you really want, I just don’t see much value.

VBT essentially means using bar velocity as a means to prescribe training intensity and therefore determine training outcomes as opposed to classic percentage-based training (PBT) or other popular methods (RPE, RIR etc.). While these tried-and-true methods have stood the test of time and been effective for many athletes, one major issue is agreeing upon what 1RM number to base your training on. It’s been suggested that 1RM can fluctuate up to 36% (18 up or 18 down) on a daily basis depending on mood, stress levels, and recovery. We’ve all had those days where the weight feels too light or too heavy. Basing your training on your all-time 1RM that you may have hit when you were in an extremely heightened state of arousal (loud music, motivation from gym partners etc.) can lead to training numbers that are way too heavy, especially when you go into the weight room on a typical Tuesday, train alone and forgot your headphones at home and are forced to listen to top 40’s pop music nonsense. Conversely, using the classic solution of training off of a training max (90% of all-time best) can work a lot of the time but can also cause you to under train on those days where you may actually be feeling good, wasting valuable training time. This is where VBT comes into play. We aim not to overtrain or undertrain, but to optimally train and VBT enables us to do just that.

Equipment

For a long time, VBT was inaccessible to most of us due to price. Fortunately, many companies have now made Velocity Tracking technology much more affordable and accessible. At Iron Performance Center, we trust Vitruve to provide us accurate and reliable data at a reasonable cost. Personally, I’ve always been fascinated by VBT principles, but either the good machines were unaffordable or the ones I had access to were extremely unreliable. Vitruve has solved both of these problems for us. There are a lot of devices on the market today. We could talk about equipment all day, but long story short we’ve found linear positional transducers to be more effective than accelerometers in our experience.

Intent and Technique

VBT’s effect on technique has proven to be an interesting caveat. Many coaches I’ve discussed VBT with think emphasizing speed will cause technique to get thrown out the window as athletes chase velocity numbers, which theoretically makes sense. Thankfully, more often than not, we’ve found that optimal technique leads to better speed anyways, so chasing max bar velocity improves technique rather than hindering it. There have been plenty of scenarios where an athlete may get slightly out of the groove on their lifts and we see the bar speed plummet, only for them to receive technical coaching and smash the speed on the following rep.

How we perform an exercise can arguably be more important than what exercise we are performing, to an extent. Utilizing VBT is especially effective with teaching athletes how to make the most of each rep as opposed to just going through the motions and getting the workout completed. Seeing quantifiable numbers in real-time provides them with a different perspective and appreciation for what maximal intent feels like, a quality they can take with them wherever they go. Even our athletes who have moved on to other schools or teams who don’t use VBT have provided feedback that they now feel they understand how to better attack each rep and get the most out of their training.

Training Zones and Qualities

Based on the work of Industry Giants such as Bryan Mann and Travis Mash, it’s pretty well universally accepted that bar speeds are related to training zones which help determine training adaptation. Thankfully, bar velocities are also highly correlated to % of 1RM. This is again a reminder that we are not looking to throw classic Percentage-Based training out the window, we’re simply reminding ourselves that 1RM’s can fluctuate daily; instead of wasting valuable training time testing 1RM’s every day, we can simply look at correlated velocities to prescribe bar load. In a perfect world you would do a load-velocity profile for each athlete for each major lift, but we’ve found Travis Mash’s work to be exceptionally accurate for most folks, +/- a few hundredths of meters per second so again a massive thank you to him for paving the way for us. With these concepts in mind, we will look at how we may use VBT to develop a variety of different adaptations. Attached below is the chart we use, again borrowed from Travis Mash, with the addition of relative typical RM Values for each corresponding % and Bar Speed.

Power

Power development is likely the most commonly understood use of VBT, and logically probably where your head goes first. Popularized by Louie Simmons, people often automatically associate VBT with power-based training. While this is one great use of VBT, we’ll discuss in future paragraphs how it can be so much more. VBT reiterates to us as strength coaches and lifters that all squats, presses, and deadlifts are not created equal. The squat may be the tool, but what are you using it for? I could squat lighter for a lot of reps and gain mass; I could squat heavy for fewer reps and develop max strength; or I could squat lighter for fewer reps and look to develop power. VBT helps us quantify this.

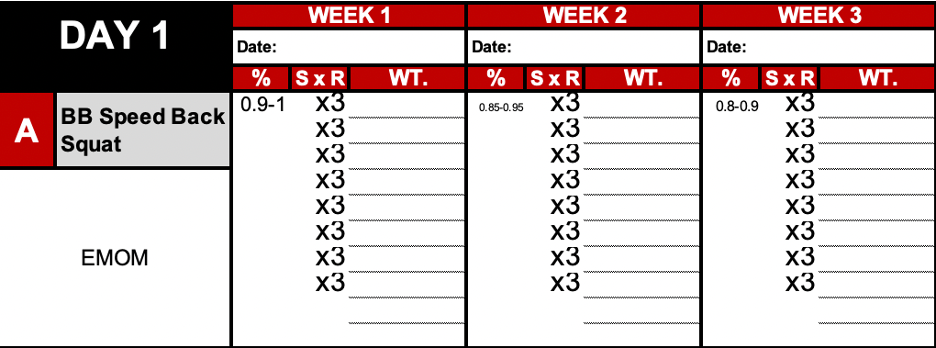

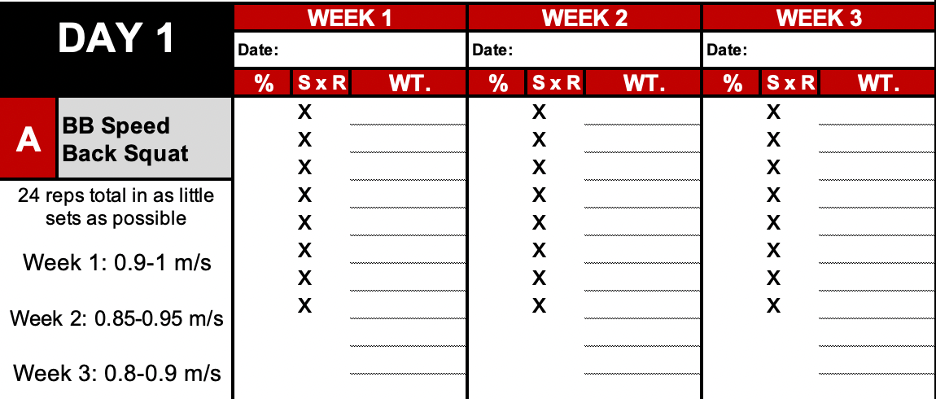

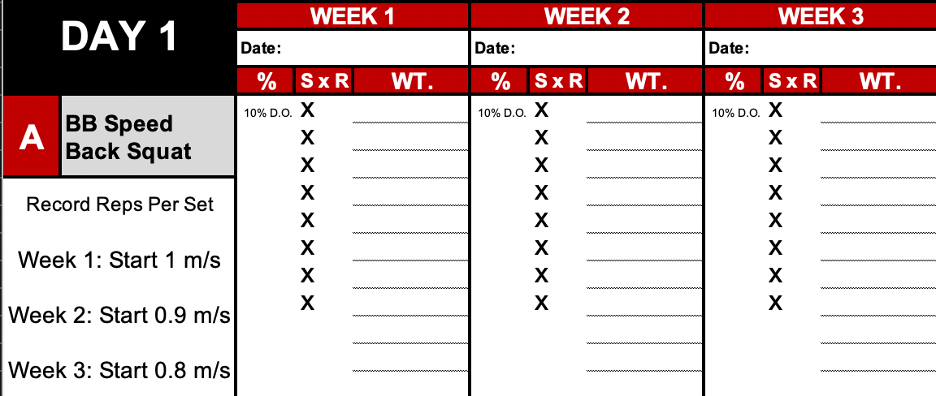

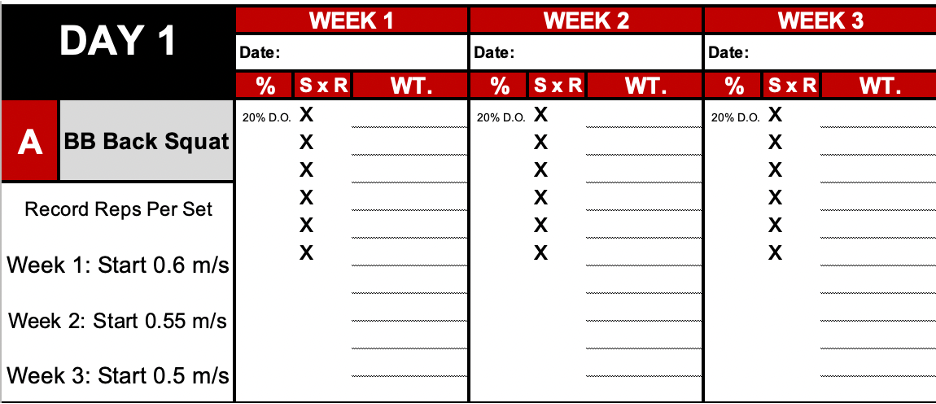

When discussing power, we will most often look to develop Strength-Speed (strength in the conditions of speed, moving a heavy implement as fast as possible) or Speed-Strength (speed in the conditions of strength, moving a light implement as fast as possible) depending on what the athlete needs most. Recalling the chart above, these reps may be prescribed in the 0.75-1 m/s range for strength-speed or 1-1.3 m/s for speed-strength. Classically, a training program may prescribe 8x3 @ 50% 1RM week 1, 8x3 @ 55% 1RM week 2, and 8x3 @ 60% 1RM week 3. Using VBT, we may prescribe something like 8x3 @ 0.9-1 m/s week 1, 8x3 @ 0.85-0.95 m/s week 2, and 8x3 @ 0.8-0.9 m/s week 3. This will allow us to prescribe loads week to week that account for daily fatigue and athlete readiness without being married to a specific percentage of an arbitrary 1RM. Using VBT will lead to some weeks where you impress yourself and lift heavier than you thought, and others where you may feel you are actually underperforming. We must stay the course and trust the process, always keeping in mind that progress is not linear. As long as we are seeing improvements over time, daily and weekly fluctuations are a perfectly normal part of the training process. Below is an example of what this may look like:

Strength

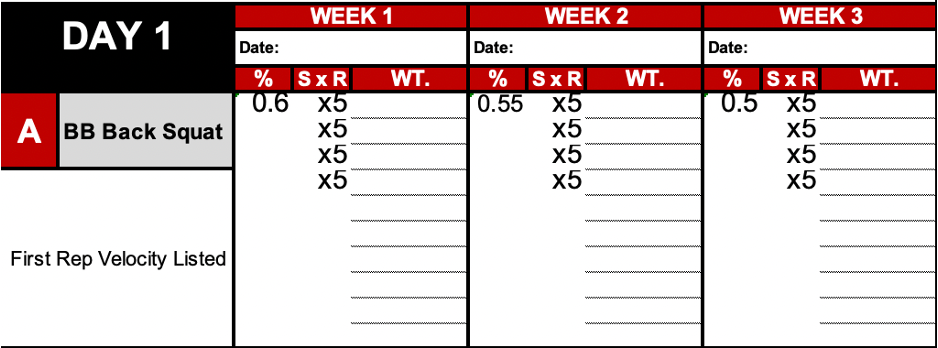

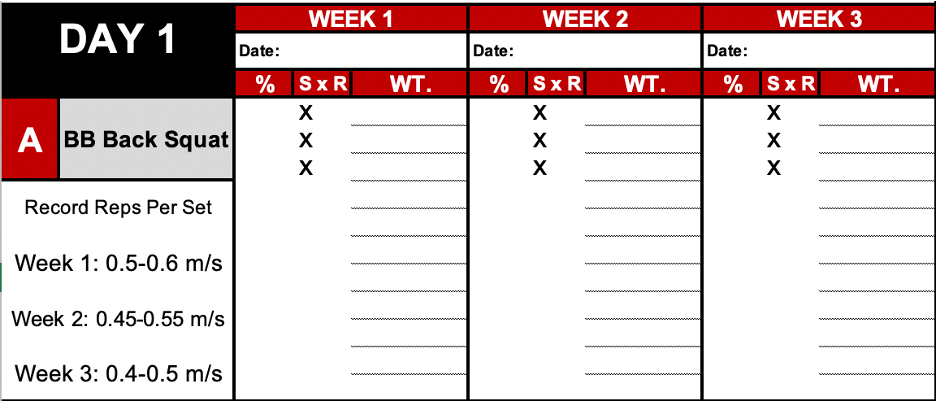

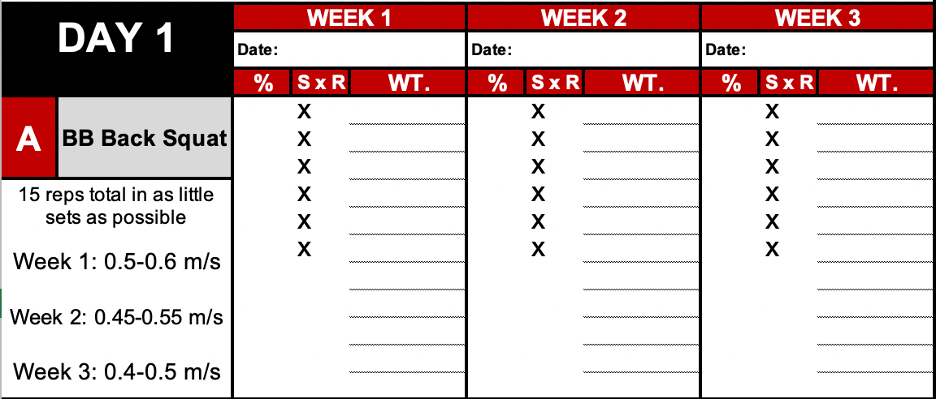

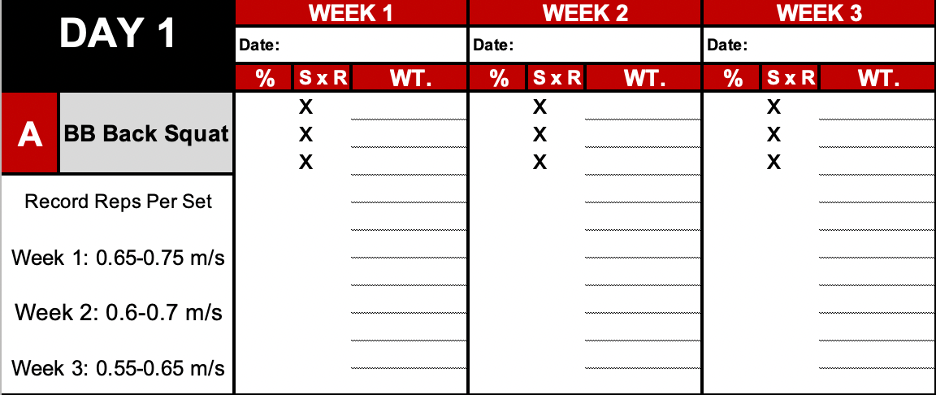

Velocity based training can also help you make informed decisions during strength work to ensure you are lifting optimally: not too heavy, but not too light either. Are the weights “slow enough” or do I have more in the tank? This can work two ways. It can ensure that we are not going too heavy on days where our 1RM may theoretically be lower. For example, instead of saying work up to 3x5 @ 80% on the squat, we may prescribe the athlete to work up to 3x5 where the first rep of the set is at 0.6 m/s. This should help us ensure that we are working at the right weight to develop strength for that day: not too hot, not too cold, just right. Conversely, this is also a great teaching tool for younger athletes. It can be a daunting task initially to help instill in them the confidence to lift heavy. Using VBT can help us educate them when they may have much more left in the tank and are able to throw more weight on the bar. When you’re a new lifter, 80% feels pretty damn heavy. While we may not need to push them all the way to 100%, VBT can help us teach them what 85-90% feels like. Below is an example of what this may look like:

Hypertrophy

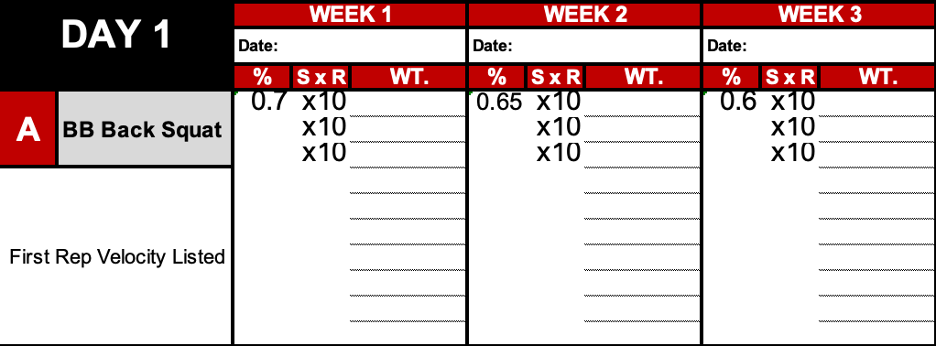

As you’ve probably realized by now, regardless of goal, VBT can help you make informed decisions about bar load. While your classic hypertrophy prescription of 3x10 @ 65% may work fine, you may be even better off prescribing 3x10 with first rep of the set at 0.7 m/s to ensure you are lifting the correct weight for that day. Below is an example of what this may look like:

Ranges and Drop-offs

Another fascinating prescription we can use is velocity ranges and drop-offs. We can use velocity drop-offs to once again ensure the quality of every rep being performed. By setting our VBT tracker (or doing some mental math) to notify us when our bar reaches a certain percentage speed drop-off, we can also greatly affect the training outcome and adaptation.

Some common drop-offs are listed below:

40% - This is typically as far as anybody can push a set before failure. While we may not use this for too many athletes, it may be necessary for those who are undersized and need to put a lot of size on or in a situation where you need to teach an athlete or client what muscle failure actually feels like. It can also be the appropriate tool for athletes who need to improve their muscular endurance.

20-30% - This is typically the sweet spot we will use for strength or hypertrophy, most often using 30% on upper body lifts and 20% on lower body lifts. Research suggests that after this point, lactate and ammonia start to build up which may cause us to develop more type I than type II muscle fibre, which for most athletes we train is not desirable.

10% - This is typically the drop-off percentage we prescribe when aiming to improve power with lighter loads, again looking to maximize and optimize the output on each rep we perform. This can also be a powerful deload tool, say in a strength phase like the third “strength” example outlined below, where we may throw a deload week in week 4 that has us lifting weights using the same starting speed but working to a 10% dropoff instead of a 20% dropoff, hereby continuing to lift heavy but naturally cutting the volume we perform.

5% - This is typically the lowest dropoff we will use and only really applies to power movements during a peaking or tapering phase.

Ranges

To apply similar principles but keep the prescription even simpler, we will sometimes simply tell the athlete or client to perform as many reps as possible in a certain velocity range as you will see below. The goal is the same; rather than simply completing the reps for the day, we can ensure the quality of each rep performed.

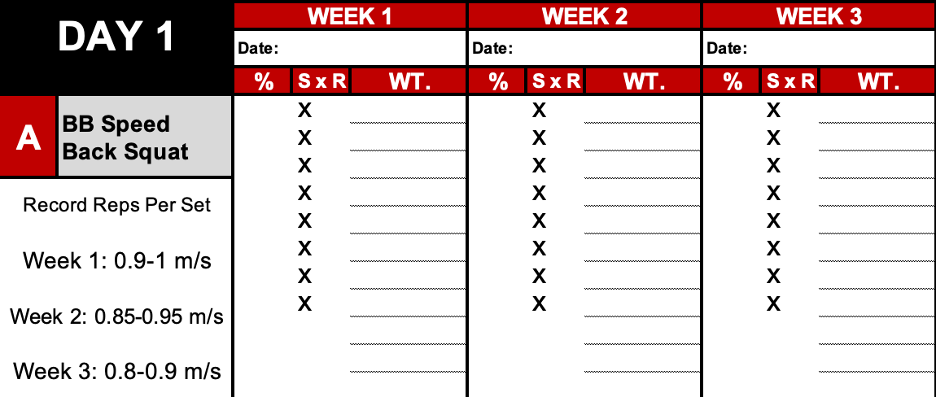

Let’s revisit some examples from above. These methods again help to optimize all reps performed while encouraging healthy competition in the training room. Ranges and drop-offs help us take these prescriptions one step further. While you may prescribe 8x3 at a certain percentage, one athlete may only hit 2 reps at the proper velocity each set and then experience a large drop-off in velocity on the third rep if they do not have adequate power-endurance. This means that 1/3 of the work they are doing is actually too slow and will not positively contribute to an improved power adaptation. You would of course never know this if you did not have a VBT device to measure bar speed. Prescribing velocity ranges can ensure that every rep performed is positively contributing to the adaptation you seek. You may either prescribe a specific number of sets and say on each set, get as many reps as you can within the velocity range. This could then be improved week to week by trying to get more reps within the same velocity ranges OR by performing a similar number of reps with a slower (heavier) velocity.

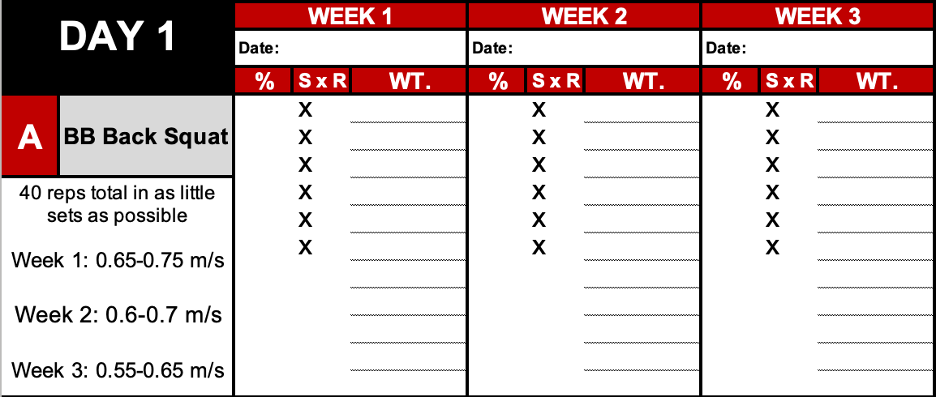

Conversely, another athlete may be able to sustain their bar speed for longer which is where ceiling reps may come into play. Why predetermine that they are going to perform 8x3 when they could get the same quality of reps (same bar speed) with 4x6? Same amount and quality of work done, half the time. In this case, we may tell the athletes they have to hit 24 reps for the day, keeping the bar speed within a certain range. This again increases competition levels in the weight room and can improve session efficiency. These concepts can also be applied to strength and hypertrophy, as will be discussed below.

Power

Instead of prescribing 8x3 at a given bar speed, we may prescribe 8 sets of an unknown number of reps where the bar speed has to stay within a certain range (potentially 0.8-0.9 m/s for power). We may either do something like 8 x ? number of reps OR set a ceiling number of reps we wish to hit for that day and get there in the smallest number of sets possible i.e. 24 reps for the day, stay between 0.8-0.9 m/s, get it done in as little sets as possible. Instead of a velocity range, % drop-offs can also be used. For power, we may say 8 x 10% drop-off with first rep velocity at 0.9 m/s. Below are a few examples of how we might do this:

Strength

Instead of prescribing 3x5 at a given bar speed, we may prescribe 3 sets of an unknown number of reps where the bar speed has to stay within a certain range (potentially 0.4-0.5 m/s for strength). We may either do something like 3 x ? number of reps OR set a ceiling number of reps we wish to hit for that day and get there in the smallest number of sets possible i.e. 15 reps for the day, stay between 0.4-0.5 m/s, get it done in as little sets as possible.

Hypertrophy

Finally, instead of prescribing 3x10 at a given bar speed, we may prescribe 3 sets of an unknown number of reps where the bar speed has to stay within a certain range (potentially 0.5-0.75 m/s for hypertrophy). We may either do something like 3 x ? number of reps OR set a ceiling number of reps we wish to hit for that day and get there in the smallest number of sets possible i.e. 30 reps for the day, stay between 0.5-0.75 m/s, get it done in as little sets as possible. Instead of a velocity range, % drop-offs can also be used. For hypertrophy, we may prescribe 3 x 20-30% drop-off with first rep velocity at 0.75 m/s.

Competition Breeds Success

As the old saying goes, competition breeds success. Using VBT can help keep athletes motivated and competitive (both against themselves and among their peers) to provide that extra push in training, even when athletes may not be at their best. It can also be invaluable for providing that extra push to athletes who may be training on their own. In a world where many young athletes love to gamify everything and spend hours on end playing video games, this can be the perfect motivational tool to meet them where they’re at and speak their language.

Autoregulation: Know When to Hold ‘em, Know When to Fold ‘em

Most people think of autoregulation as a means to peel back and train lighter, but it’s equally important to be able to crank up the intensity and “get it while it’s hot,” so-to-speak. These decisions can be made based on a seasoned coach’s eye and guided by a strong gut feeling, but can be validated by what the VBT device tells us. It can help us keep the leash on the athlete when they think they may be able to go heavier but the velocity tells a different story, or it can be used to ramp up and encourage them to send it on those good days! In the same way you may use a variety of tests to determine daily readiness through a variety of tests like force plate jumps, IMTP, or grip strength measurements, you can use VBT to assess readiness. Wil Fleming has discussed performing a muscle snatch in the warmup with a standardized weight and using it as a daily baseline, for example. If you know how fast the athlete moves a fixed percentage of their 1RM on any of the big 3 lifts (say 70% of their 1RM back squat always moves at 0.67 m/s), that rep will probably be built into their warmup anyways so you can reflect on how they are moving that weight that day to determine if training loads should be increased or decreased. If it’s moving way faster than normal, increase training loads; if it’s moving way slower than normal, decrease training loads. It can be that simple!

Validation

Implementing VBT can help foster and improve the athlete-client relationship. There are those days where you know the athlete has more in them and may just be going through the motions, and again VBT can help validate this. An athlete may think you are picking on them, but having the numbers to back up your coaching points can only help.

Progress Measurement and Predicted 1RM’s. Wattage

A hotly debated topic in the S&C realm is whether or not athletes should test 1RM’s in their lifts. While both sides make valid arguments, VBT can help to quantify improvements in strength without always having to take an athlete to failure. It’s been suggested that every increase in speed of 0.05 m/s can be equated to a 2% increase in strength. If you know an athlete can move a certain weight as their 1RM at 0.2 m/s, and after completing your training program they move the same weight at 0.3 m/s, we can extrapolate that they’ve gotten roughly 4% stronger in their 1RM without having to test it (assuming technique and tempo are equated). Many VBT units out there and their associated apps will have 1RM testing modes. Keeping in mind that bar speed and 1RM share a linear relationship, these apps can have athletes lift progressively heavier weights up to around 80-85% of their predicted 1RM and calculate, pretty reliably, what their 1RM is. This is yet another way VBT can be used to help athletes lift safely and optimally. You could also use a static load to track an athlete’s wattage output at a specific bar load to see if it improves over time, assuming power output is a goal of theirs.

Programming

Remember from the beginning that we are not trying to reinvent the wheel here, but simply trying to find better ways to use the one we already have. We’ve outlined some decent programming parameters and ideas above, but of course you are always free to use your imagination as well, experiment, and see what works. Instead of scrapping everything you’re currently doing and starting from scratch, you should likely be able to take the program you’re already doing and apply VBT principles to it. I’m still in the trenches learning and optimizing every day; these thoughts above are simply my own recollections of what’s worked thus far in our setting and will serve as groundwork for my athletes’ training to come. I look forward to having coaches read this article and having an open dialogue with them as well so I can learn more ways to use VBT. Again, none of these concepts are original and have all been borrowed from the industry greats.

Alternative Uses

VBT is also a fun tool for older lifters. Former athletes love opportunities to feel explosive and competitive. Research suggests that power declines rapidly with age, so we can use VBT to safely and effectively maintain or even continue to develop this quality.

Another unexpected advantage we’ve experienced is in the context of return-to-play. We can use VBT numbers we have on record for each athlete to compare pre-injury to post-recovery performances. While it may be a bit of a stretch to tell the athlete, “You squatted 100 kg at 0.8 m/s pre-injury and can now do that again post-recovery so you’re ready to hit the field again,” it can certainly enhance their confidence and help them quantify the RTP process.

Finally, from a structural balance perspective, we’ve paid special attention to side-to-side velocity imbalances on exercises like split squats and reverse lunges. No matter what style of programming you follow, most coaches believe in doing our best to limit side-to-side or front-to-back discrepancies in our athletes, so VBT could potentially provide another opportunity to quantify this. This is something we’ll have to explore further, but for now it’s certainly thought-provoking.

Conclusion

As you can hopefully now see, there are plenty of ways we can use VBT to quantify and enhance the work we are already doing. Of course we know no tool is perfect. Sound programming and coaching will always be of utmost importance; VBT incorporated properly simply helps us enhance these two factors. Instead of just going through the motions and getting the work done, we can quantify the quality of every single rep of the day.

Subscribe to our blog

Subscribe to receive the latest blog posts to your inbox every week.

Related posts

Implementing French Contrast Training In A Group Setting

A Simple & Efficient Way to Test Gains In-Season