A Simple & Efficient Way to Test Gains In-Season

As Strength & Conditioning Coaches, we live and die by numbers. Who is benching the most? Did their squats increase? What is the freshmen’s body weight looking like? Did they get faster?

All of these are data/number-driven questions and their answers can often tell you if you are doing your job or not. Unfortunately, we all know it comes down to relationships with your athletes, how much they buy in, and how well you drive culture and intent, but, until they figure out a way to quantify those as useable metrics for admin and coaching staffs, we will just have to stick to our good ol’ fashioned numbers.

So what numbers should you look at? What matters?

Well if you can look at key performance indicators such as sprint times and jump heights, I would highly recommend those. While putting up big numbers in the weight room is great and is part of your job, if they are not getting faster or jumping higher, then they are not improving as an athlete, which is what really matters for their sport.

But how else can you quantify your role in an athlete’s development in the weight room? What do you do when sport coaches want to know about their team’s squat or bench numbers? Well, you could do the old 1RM test, right? Sure, but we all know that can be risky at best, even in the off-season. So how do you show your kids are getting better even in-season efficiently without increasing injury risk?

I want to share what we have been doing at Trinity Western University over the last year and how it has been a game-changer for us.

We’ve been using Velocity-Based Training devices for our testing (linear position transducers, LPT, to be exact), but probably not the way you are thinking. Often coaches use a set 1RM percentage (ie. 80%) and get athletes to move that load as fast as possible to track their progress in strength. While that idea works, I wasn’t happy with how long those testing sessions would take to change the load on the bar plus 80% feels like 90% to some and 70% to others, depending on the day.

So, what do we do that has been so simple and effective?

I’ll lay it out for you.

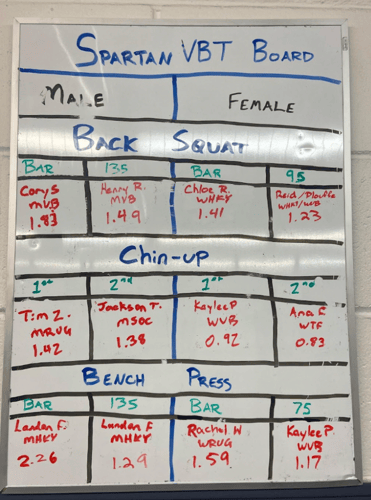

We do three tests - Back Squat, Bench Press, and Chin-up.

We have a set load for males and females and they record their fastest single rep.

The weight on the bar is:

Males:

Back Squat - 135 lbs

Bench Press – 135 lbs

Chin-up - No added weight

Females:

Back Squat - 95 lbs

Bench Press – 75 lbs

Chin-up - No added weight

For example, a testing session looks like…

The team rolls into our weight room (named Sparta). We do our team warm-up (6-8 min) and start testing. We have 5 racks, so 2 are designated for squats, 2 for bench, and 1 for chin-ups. We let athletes do warm-up sets if they want (which most of course do not), and then they load the appropriate weight on the bar (see above). They can try each exercise as many times as they want, and then simply write down their best score in meters/second (m/s) on a printed-out scoresheet (which I upload to an Excel document to send out later). For the chin-up one we just take a bungee cord to make a belt for the LPT to attach to for their rep. If they can’t get a bodyweight chin-up, they simply get 0, which means any rep they do get will give them a score to track progress with.

So why is this way of testing so great?

- The whole session takes 15-20 min (logistics)

- It acts as a great Power training session as no one slacks when a recorded score is on the line (plus it enforces proper rest breaks by having people wait until a station is open)

- This can be done as frequently as you want it is non-fatiguing and doesn’t cause DOMS (as long as you have been using these exercises in your normal training).

- The constant weight across teams & genders allows me to compare who the “big dogs” on campus are (which everyone wants to know)

- For this, I keep a Spartan VBT Leaderboard with top athletes for each lift (see below)

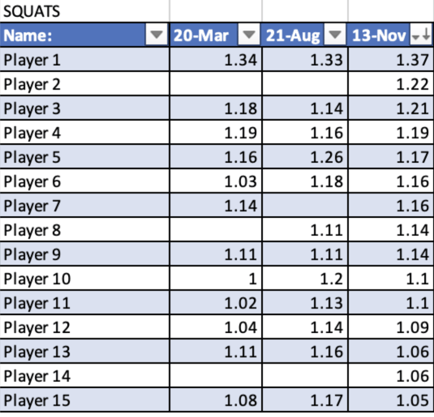

- It allows me to rank athletes within the team for the coach to see

- Easy to see progress for everyone as the weight stays the same

The idea/concept comes from the fact that if you train and get stronger, the set weight (ie. 135lb) becomes a lower percentage of your 1RM, which means you should be able to move it faster. Simple. Effective.

The weights I’ve set have come from experiencing the athletes we have on campus, and what they can and can’t do. So the 135 lbs for males and 95/75 lbs for females isn’t validated by research, just what our athletes can comfortably do here as I’ve seen over my time here. Do some athletes struggle more? Yeah, of course. For some of them, it is closer to a 1RM that I would like, but no testing plan will be perfect and those athletes that struggle heavily are very few and far between (and much less than in a 1RM or 80% situation) so we keep rolling with it.

The data gets sent to the coaches and they can see who is the “strongest” based on this method, as well as who has progressed or not easily (see image below).

Once again, this is not some revolutionary idea that no one else has, but just something I wanted to share as I have been in the same boat as many of you where coaches are demanding results, you are strapped for time/space, and don’t want to injure your athletes for the sake of a testing number or your ego. I found that this cuts through the middle and gets the best for everyone. You get good progress data, athletes can see who is the “big dog” and coaches can see who is working and making gains.

Again, it all comes down to your population for the weight you choose. If you are in a High School, you might want to choose a lighter weight than I did. If you are in a pro setting or working with a college football team, you might be able to ramp up the set weights. The key is to keep it consistent, test frequently, and show them the data so they know if they are making gains or not. We test 4 times a year (training camp, before winter exams, New Year, Spring) and have seen some good progress so far.

Now I am not opposed to getting athletes to “do hard things” and using this as a way out of pushing my athletes. Far from it, in fact. But I would rather push them in their actual lifts and make the testing more of a quick checkpoint to see that we are on the right track as opposed to having the ensure they sleep well, get psyched up, and drink caffeine all in the hopes they can lift 5 more pounds without breaking their back. Plus this cuts the anxiety in half (at least) around testing.

So if you are looking for a new, efficient, and safer way to test your athletes, or you have coaches breathing down your neck to give you some data, this is a pretty easy way to provide what they need.

(A caveat to this all is you need VBT units, which your department may or may not be able to afford. We use Gravity Box units. Highly recommend checking them out!)

Subscribe to our blog

Subscribe to receive the latest blog posts to your inbox every week.

Related posts

The Power of Microdosing

Don’t let the Appetizer Spoil the Main Course: Tips for Effective In-Season Basketball Training