A Performance Guide to Managing Transmeridian Travel – Part II

Travel forward in time from Part I of this series. Three years have passed. The members of the U.S. Freestyle Moguls team are improving practices and habits. The team has had some success in that time, including over 30 World Cup podium performances and three World Ski Championship podium performances. We are on our way.

Our plan for travel around the globe is substantially improved. When things go smoothly, we handle travel well and when they don’t, we seem to shine. In December of 2019, we had two World Cup Events. The first, in the aforementioned, Ruka, Finland and a second in Thaiwoo, China. The events were a week apart and so, in a matter of two weeks, we will have circled the globe and competed three times.

Thaiwoo, China is small ski resort about four hours by bus northwest of Beijing. To get there, we drive toward the Mongolian Border to where the Great Wall of China traverses the mountain terrain atop the resort. In this remote location time has reduced the wall to a pile of rocks, but it is pretty incredible none the less. Many of the events in the upcoming 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic Games will be held in this region. It is a bitterly cold environment but snows surprisingly little. The vast majority of the snow at the resort is man-made. When it does snow, things get a bit hairy.

Our trip to Thaiwoo in 2019 was a fruitful one; we walked away with a few podiums and had just finished a workout in the third floor of an adjacent hotel. Feeling satisfied with a good day, I returned to my room to pack for our scheduled departure the next morning at 6:00am. I retire to bed around 9:00pm and fall soundly to sleep.

“Get up and get downstairs! The bus is leaving in 30 minutes!” All of the sudden, my roommate, our assistant mogul coach, wakes me with a shake and urgent yell. I am out of it. I immediately think I have overslept my 5:30am alarm. Not the case. It is 10:00pm. We have been notified by our Chinese aide that a snowstorm is quickly approaching and if we do not leave immediately, we risk missing our flight out of Beijing the next day.

I spring into action and get to the bus. We board and hastily get on our way. The bus driver speaks no English. He is also an accomplished chain smoker. The windows on the bus don’t open, it’s frigid outside, and after just a few minutes the bus begins to smell like a Las Vegas casino. The driver plows through a pack or two of cigarettes in the first three hours of the drive. Just before 2:00am we pull into a desolate truck stop outside of Beijing. Everyone is tired and desperate for some fresh air. After a short bathroom break, we re-board the bus; eagerly anticipating the completion of the final 30 minutes of travel to Beijing and the salvation of a hotel bed. One problem. The bus doesn’t move. As best we can understand, we have stumbled into a law that prohibits mass transit from operating in China between the hours of 2:00am and 5:00am. We are stuck. The driver doesn’t sleep; rather, he pours through another pack or two.

During that time at the truck stop I learned something about our team. They could have complained or wallowed in their own smoke-filled misery. Instead, they got out a soccer ball. First a game of duff, then a full-fledged game erupted in the parking lot. Athletes from other countries had joined in as had some of the coaches. It was a moment I won’t soon forget.

At 5:00am the bus was back on the road and 30 minutes later we were checking into a hotel. The hotel stay lasted just long enough for me eat the free breakfast and shower before boarding a shuttle to the Beijing airport. With that, we would be home for Christmas.

The question then becomes, in the face of such adversity, how does such a response take place? Is it organically formed or is there some training that enables its formation? The answer, likely, both. Here is what we did to prepare.

Our Two-Pronged Approach

Our goal was simple – we wanted to provide our athletes with big picture information and then, at the onset of each trip, engrain the details.

TEAM EDUCATE

To provide the athletes and staff with the necessary information to manage their global practices we use what we call a “Team Educate”. Team educate sessions cover a variety of topics from culture, values, and philosophy to nutrition, sport psychology, and of course, managing travel. They are typically implemented in lecture and round-table format. Occasionally, I speak. More often, I invite a content expert. For our Winning the Travel Battle session, Dr. Bill Sands was present to assist the team.

Below are the big rocks. This is far from our exhaustive list nor is it all peer-reviewed, but rather, a combination of anecdotal and literature-based evidence I would consider the bare minimum to winning the travel battle. My good friend Al Jean would call the lines below - wisdom.

STAY POSITIVE

First and foremost, if you do nothing else, do this.

KEEP A POSITIVE MENTAL OUTLOOK!

As noted in Part I, mood state is heavily affected by sleep deprivation (Inder, Crowe, & Porter, 2015). We instruct our athletes to separate their feelings from their emotions. Emotions can and will run high during periods of stress; in a way their manifestation is uncontrollable. However, we can control our feelings with a conscious effort. I have heard coaches describe this as “fake it ‘til you make it”, “dig deep”, or “embrace the suck”. Finally, we instruct them to expect things to go poorly. That way, when they do, it simply meets their expectations. They aren’t surprised by the inevitable curve ball that comes with transmeridian travel.

TRAVEL HYGIENE

Second, practice proper travel hygiene. Airports and airplanes see over 4 billion passengers each year (International Civil Aviation Organization, 2018) and they can be a formidable obstacle to athlete wellness. First, we advise the team to practice good general hygiene. The usual stuff, wash your hands, avoid touching your face; all the basics. If they are unable to wash their hands, they are instructed to use hand sanitizer (see packing lists below). Also, we advise them to wash their faces with soap and water. In addition to cleaning the face, this can improve the athletes’ level of wakefulness after a long flight.

Upon taking their seats athletes are instructed to wipe the immediate area with a Sani-wipe. Areas that should wiped include:

- Television

- Arm Rests and buttons

- Tray table and seat back

- Cell phone and other electronic devices

- Items handled by other people such as passports

Upon arrival at the final destination, athletes should shower and change clothes. This is a game changer. Not only does the shower cleanse but it will also help the athlete wake up or fall asleep depending how they set the temperature! Some of our athletes and coaches even do this at the airport lounge during connections on long haul flights.

NUTRITION AND HYDRATION

Athletes will experience a significant reduction in activity during transmeridian travel (Meir, 2002). Therefore, they should adjust their fueling accordingly. We instruct our athletes to reduce their caloric intake. Our dietician works with each of them individually to help them manage nutrition during travel as well as navigate the availability of unfamiliar food in a foreign country. As a coach, monitoring body weight and skinfolds can be your friend during a long season. More acutely, here are the takeaways:

- Aim to consume smaller meals.

- Mealtimes should coincide with the destination!

- Avoid alcohol consumption.

- Avoid caffeine intake – unless you are trying to remain awake upon arrival.

- Supplement with Valerian Root or Melatonin to assist with sleep.

- Sleep times should coincide with the destination!

- Consistently sip a hydrating drink such as Skratch, Liquid IV, or Nuun Hydration.

TRAVEL CHEAT SHEET

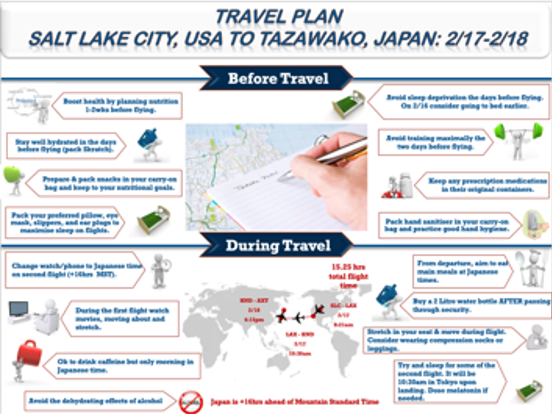

In addition to sharing a global view with the team we also provide them with a travel cheat sheet. The current format I am using (Image 1) is adapted from a good friend Mitch Pemberton, of the ACT

Academy of Sport in Australia. The purpose of the cheat sheet is to provide the specific details of our current training camp or competition. It is sent in infographic form. The cheat sheet contains four primary sections: 1) in advance of travel, 2) during transit, 3) carry-on baggage checklist, and 4) checked baggage checklist.

TRAVEL PLAN

The travel plan, as inferred, provides our flight and ground transportation schedule. More importantly, it details the following key adjustments the athletes need to make. First, the timing of light and dark exposure. Timing of light and dark exposure dictates the onset of sleep (Meir, 2002). It has a direct impact on athletes’ ability to adjust to the new time zone.

INSTRUCT YOUR ATHLETES TO STAY AWAKE UNTIL A NORMAL BEDTIME THE FIRST NIGHT IN A NEW TIME ZONE!

Failure to accomplish this task is a recipe for a trip to the pain cave. To assist your athletes in this process and the timing of melatonin or valerian root supplementation I recommend using the website Jet Lag Rooster. Jet Lag Rooster is a free service that does all the leg work of light and dark exposure for you.

PACKING LIST

Finally, send your athletes a packing list. Not one that consists simply of their practice or competition gear. A complete list. Nothing is more stressful to an athlete than forgetting their toothbrush or heaven forbid they forget their phone charger. Prepare for the optimal and inevitable challenge! Here are some recommendations for your carryon baggage:

- Essential training or competition equipment (i.e. ski boots)

- Noise cancelling headphones

- Hand sanitizer and Sani-Wipes

- A change of clothes

- A miniature toiletry kit

- A sleep kit that includes

- a pillow (suited to what kind of sleeper you are!)

- Eye mask

- Sleep aid (melatonin or valerian root)

- Ear plugs

If you are like me, at this point you probably want the nitty gritty details. I am happy to send them your way. I am also happy to work with your staff should you desire. Please free to contact me via email JBullock.Publications@gmail.com or through my website at https://joshbbullock.wixsite.com/joshuabbullock.

In the final part of this series, I will explore the best ways we can help our athletes in our traditional role as strength and conditioning coaches. We will dig into the movement-based interventions, how I plan and prepare as a coach, and the specifics of program design and implementation I employ to assist our team in pursuit of their dreams.

Bibliography

Inder, M., Crowe, M., & Porter, R. (2015). Effect of Transmeridian Travel and Jetlag on Mood Disorders: Evidence and Implications. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Phsychiatry, 1-8.

International Civil Aviation Organization. (2018, March 9). ICAO Statiscitcs. Retrieved from https://www.icao.int/annual-report-2018/Pages/the-world-of-air-transport-in-2018.aspx

Meir, R. (2002). Managing Transmeridian Travel: Guidelines for Minimizing the Negative Impact of International Travel on Performance. Strength and Conditining Journal, 28-34.

Subscribe to our blog

Subscribe to receive the latest blog posts to your inbox every week.

Related posts

A Performance Guide To Managing Transmeridian Travel - Part III