A Performance Guide to Managing Transmeridian Travel – Part I

Flash back to December 2017, four months earlier I was hired as the Athletic Development Coach for the U.S. Freestyle Moguls team and had never traveled more than three time zones for competition. The story that follows is entirely non-fiction. Trust me, the literature can’t cover the real world and you can’t make this up.

It was the evening after the first World Cup event of the season; a season of particular importance as each event represents an opportunity to qualify for the 2018 Winter Olympic Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea. The team had performed well that day in the 21 hours of darkness that descends upon Ruka, Finland each December; but we are looking forward to seeing some daylight.

We boarded a bus at 1:00am for the 3-hour bus ride to Oulu, Finland; we are on our way back to Utah for two nights and then on to Thaiwoo, China for the next event on the World Cup tour. Around the world travel is the norm for the team. The bus was nice, but let’s face it, there is no replacing a bed, even if it isn’t your own. After three hours of head bobbing, we finally arrive at the Oulu airport to discover a ghost town.

We have arrived so early that the airport employees don’t even clock in for work for another hour. 50 pieces of luggage checked by two employees and we were off to Amsterdam’s, Schiphol International Airport.

Schiphol International Airport has large, beautiful windows down both sides of the terminal, perfect for viewing the snowstorm as it rolls in. As we wait in line to board the plane, airport personnel seem positive about our timely departure, but my gut feeling is telling me otherwise. The designated boarding time comes and goes like a blur. I can see a few other planes pushing back which is keeping my flame of hope alive. Slowly everyone in line goes from standing at the ready, to leaning against the wall luggage on the floor, to sitting against the wall feet propped up on carry-ons. After about 2-hours of sitting on that wall we board the plane for our flight back to the United States. I am as good as home. I walk the length of the plane to find my seat. Being new to travel I don’t have the airline status, so I am at the rear but in a window seat, making it rather easy for me to view our impending demise.

The plane doors close but the minutes begin to drift by like the swirling snow that is piling up outside my window as we wait to push back. First, 15 minutes, then 30, then an hour, then two, then four. With every passing minute I grow more and more impatient. I can feel the anger grow with my level of hunger. I am text messaging my wife as we sit and wait. She has talked me off the cliff of despair no less than half a dozen times. Finally, after six hours we push back. We are told that we will be going to de-ice the plane and then depart for our trip across the Atlantic. Again, the minutes begin to pass. First, 15 minutes, then 30, then an hour. I sit in utter disbelief. After two hours we begin to de-ice the plane. As we undertake the process the captain informs us that if we do not take off within the next 30 minutes we will be forced to return to the gate. Evidently, regulations prohibit pilots from being at the helm and on the ground beyond a certain time period to ensure passenger safety. Despite the intention to persevere life and avoid the worst I am blinded by my anger. I cannot believe that after all this we would simply turn back to the gate. Then we do. Our time has run out and the captain informs us that we will be returning to the gate.

One problem. The gates are all filled with other planes that are unable to depart and the number of planes needed to be moved far exceeds the number of tugs available to move them; so, we wait, again. I am beside myself. Upon further reflection, I am also completely irrational. As we wait, yet again, the minutes pass by. First, 15 minutes, then 30, then an hour. After two hours the plane arrives at gate. Our 10-hour “plane ride” has netted a grand total of zero air miles, maybe a mile on the ground, and has left us no closer to home. As I de-plane, one of our assistant coaches can see my mood-state, he is wearing a big smile, he prods me, and it works. I finally explode in hunger and frustration.

That night I sat in my hotel room, albeit for just a few hours as we were readying ourselves to try again the next day, I reflected on my attitude, behavior, and as the purpose of this article, my preparation – or lack of it. I urge you to learn from my mistakes and the over 126,000 miles a year behind this article. I am hopeful this story leads to you establishing a plan for both yourself and your athletes. Share the information in this series of articles with them, teach them how to manage themselves, give them the tools to win in the travel battle.

Current Literature

Before we get into the nuts and bolts of day-to-day practice, here is what you need know. Jet lag is associated with rapid air travel across three or more time zones and in the literature is primarily attributed to disruptions in circadian rhythm (Inder, Crowe, & Porter, 2015).

The typical symptoms associated with jetlag include but are not limited to (Dragoo, 2012; Meir, 2002):

- Sleepiness/Sleep Disruption

- Fatigue

- Changes in Mood State

- Loss of Appetite

- GI Disturbance

- Disorientation/Loss of Concentration

- Loss of Drive

- Discomfort/Malaise

- Headaches

It goes without saying the above characteristics and symptoms appear less than desirable when it comes achieving a high-level performance. So, how do they affect your athletes’? That to seems to depend. “Data supporting a decline in performance following travel are not always confirmatory” (Dragoo, 2012, p. 565). To make things even more confusing, athlete perception doesn’t always match athlete performance. In a study by Bullock et al (2012), athletes perceived themselves as jetlagged for 7 days but experienced no significant decrement in sprint performance (Alhola & Polo-Kantola, 2007).

To make some sense of this material, some studies have attempted to differentiate the effects of jetlag based upon the direction of travel, east to west vs. west to east. These studies have had differing results. Additionally, athletes and coaches may be unable to control for training time and rarely, if ever, have control over the competition schedule as such considerations are controlled by television, facility availability, light considerations, or other extraneous factors. Finally, athletes and coaches rarely have control over their travel schedule; as they are subject to flight, train, and bus schedules or the inevitable delays that come with transmeridian travel. Optimizing training and competition times to meet circadian rhythm is therefore, largely, impractical.

Perhaps more reliably the coach should consider the effects of sleep deprivation, mood state/stress, and fueling interventions on performance. While also acknowledging sleep deprivation in their teams and/or athletes as either acute or chronic and total or partial. In other words, control the controllable.

The effects of sleep deprivation on performance are widely studied in many populations including medical personnel, military personnel, and athletes. Generally speaking, performance can be broken into two categories: cognitive and motor abilities. Sleep deprivation, appears to have less of an effect on motor abilities when compared to cognitive ability or changes in mood-state (Dragoo, 2012) with endurance measures being more sensitive than strength and power. For example:

- In a study by Souisi et al (2003), anaerobic power variables were unaffected after 24 hours of sleep deprivation; however, they were impaired after 36 hours without sleep.

- Reilly and Piercy (2007), have demonstrated minimal effect on maximal effort weightlifting following 2 nights of successive sleep restriction. Submaximal efforts were affected to a greater degree than maximal efforts.

- In a study by Kerimidas et al (2018), military cadets conducting two days of sustained operations with partial sleep deprivation demonstrated a 29.1% decrease in cardiac output.

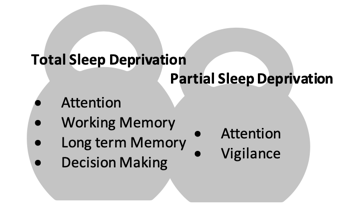

The effect of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance appear unpredictable and task-specific (Jackson, et al., 2013). Broadly, both total and partial sleep deprivation induce decrements in cognitive performance although the degree may vary based upon age and gender with substantial individual differences. The graphic at right, although not intended to be exhaustive, provide some insight as to the performance factors affected (Alhola & Polo-Kantola, 2007).

Several studies have shown that elite athletes have sleep loss and mood disturbances following transmeridian travel (Waterhouse, Reilly, Atkinson, & Edwards, 2007). The fact that mood is most adversely affected by sleep loss is not surprising and has been studied in a number of populations ranging from cancer patients, mental illness patients, adolescents, college students, the elderly, and elite athletes. As a coach you can expect the following subscales to be significantly worsened following one night without sleep (Pilcher & Huffcutt, 1996; Inder, Crowe, & Porter, 2015):

- Depression

- Anger

- Confusion

- Anxiety

- Vigor

- Fatigue

Finally, the coach needs to be aware that athletes will be less active during extended periods of travel. During flight, “the body will effectively be in rest mode and will therefore not require the same amount of food it normally does” (Meir, 2002, p. 33). Hydration status may also be compromised by the dry air in the pressurized cabin and therefore, contribute the exasperated jetlag upon arrival (Meir, 2002).

In Part II of this series, I will explore the interventions that can be applied improve performance outcomes as well as share some anecdotal evidence and experience. Finally, I will share some of the resources I have used over the past three years with my team to ensure we win the travel battle.

Subscribe to our blog

Subscribe to receive the latest blog posts to your inbox every week.

Related posts

How Music Enhances Athletic Performance & Training

Fitting Speed Training Into Your Practice Schedule