3 Common Deadlift Mistakes Holding Your Athletes Back

One of the most important, if not THE most important, movement patterns in a long-term athletic development system is the hip hinge. All the cool kids refer to these as deadlifts. A loaded hip hinge movement, the deadlift is essential to all strength & conditioning programs.

While extremely beneficial to our athletes’ progress, it’s also a highly technical movement that can be tough for athletes to master. Some struggle with the ability to initiate movement at the hip joint versus a much easier squat pattern, which is knee dominant.

We can smooth out this learning process by eliminating the three very common deadlift errors below. Helping athletes avoid these mistakes and maintain proper deadlift form will give us stronger, more resilient athletes at a much faster rate.

Incorrect Variation for Athlete

The first and most common deadlift mistake is using the incorrect deadlift variation for the lifter. This is more of a coaching strategy, but it’s also great to teach this to the athlete as well. This helps build autonomy and solidifies their relationship with training.

The conventional stance barbell deadlift from the floor is a great lift. It’s one of the mandatory options for competitive powerlifting meets. It’s absolutely NOT mandatory for athletes who want to get bigger, faster, stronger, healthier, etc.

Force feeding incorrect variations into our programming is a recipe for disaster. To fix this issue, we have to utilize the variables available and find the safest, most beneficial deadlift for each individual. Most of all, we need to use the variation that addresses weaknesses in the most powerful way.

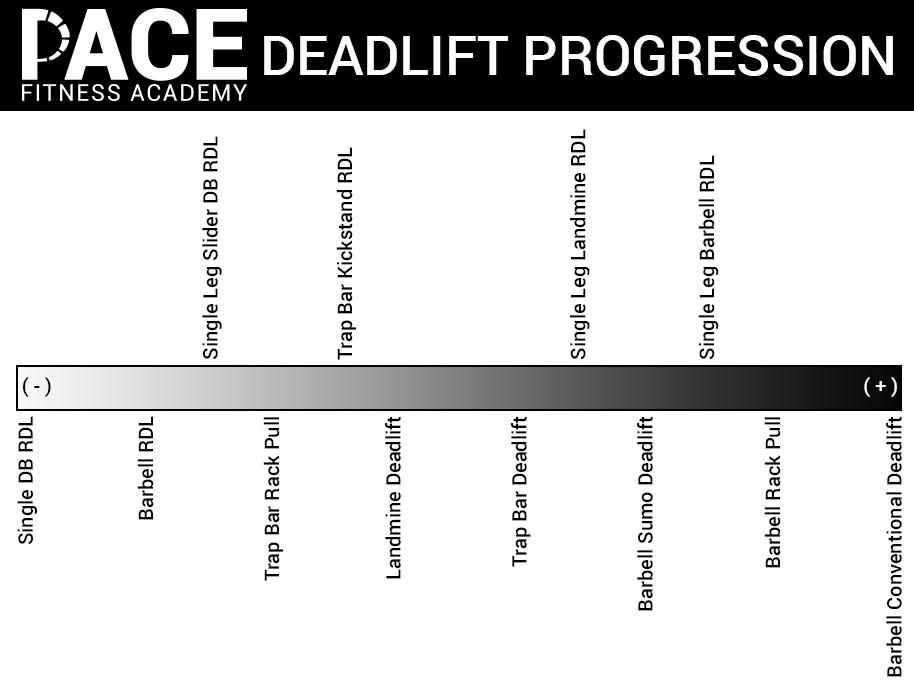

I use the following progression sequence for loading up hip hinges with athletes from ages 8 all the way up to 65.

From left to right, we see the least advanced to the most advanced versions of deadlifts that I currently program. Sure, there are some outliers not shown. And, yes, “advanced” is a general blanket statement combining mobility, experience, confidence, strength, time as my client, etc. You get the point.

I may throw in something not on this list, or have a client skip multiple progressions based on their assessment – but this is a tool that I feel can be super useful for anyone looking to make true progressive steps.

I think it’s always a better idea for athletes to master a movement pattern, rather than mastering a certain lift. We master the hip hinge, not the competition deadlift.

Probably the simplest way to fix this issue is to simply have a system in place that caters to individuality. I am not in a school setting, so I know I’m a little spoiled when it comes to this. I have 5 to 10 kids in at a time for lift sessions. High school coaches may have 100 in at a time. Team coaches may have 12 to 60 athletes in at a time. I understand that in these ultra-packed settings, not everyone can get a full diagnostic assessment, but having even the most basic screening protocol can be so helpful.

Using the baseline assessment data to strategically program, progress and regress athletes through your system will help smooth out the process. This will help eliminate fitting a square peg into a round hole, making it a safer and more advantageous training experience.

Confusing Clean Set-Up with Deadlift Set-Up

Athletes deadlift. They also perform clean variations. The two can appear to have a similar setup in the eyes of our athletes. In reality, these lifts have extremely different setups, different outcomes and train different adaptations.

The conventional deadlift setup, although different for everyone, will generally have a more vertical shin angle, bar over the shoe laces, feet about hip-width apart, most of the time shoulders above or slightly in front of the bar (and some people will scream that they should be behind the bar, that’s fine too) and hips elevated to the midway point between shoulders and knees. In a deadlift, you want to maximally load tension into the posterior chain and that setup allows us to do so.

In a clean, we see a little bit of a more positive shin angle, a more vertical torso angle and – the biggest difference – the hips are about even with the knees, with quads pretty much parallel to the ground.

Efficient deadlifts require a linear bar path. Cleans do not end at the hips like a deadlift, so a linear bar path won’t work. A clean will pass the knees, come to the hips and then continue up with addition force from hip contact to be received in the front rack position – more of a “S” shaped bar path.

So, why doesn’t the clean setup work well for a deadlift? The knees get in the way. Deadlifts are much heavier by nature, so you want to create a mechanical advantage by creating a linear bar path. Get from point A to point B as fast and strong as possible. If you setup with a deadlift load in a clean stance, you’re required to take that heavy load through a non-linear bar path with is way less efficient because you have to bring the bar in front of and out of the way of the knees.

The other option, which is what is so common, is to straighten the knees early to get them out of the way. Yes, this gives a linear bar path, but extending at the knee while the bar is still under the knees moves all maximal tension from hamstrings and glutes into the lumbar spine and surrounding muscles. Not a good plan. Both options force you to direct shearing forces to the low back, which is not only ineffective but also extremely unsafe.

As a coach reading this, you’re probably like, “Yeah, duh!” but this is a really confusing thing for athletes to grasp at first. And it also works both ways. A deadlift setup won’t work well for a clean. Humans naturally gravitate to the path of least resistance. We do what we’re good at. Sucking at something… well, sucks!

So, if I’m a 17-year-old football player who crushes cleans, but struggles at deads I’m going to try to deadlift with what I’m good at – a clean stance. It’s just up to us as coaches to be there to catch it, correct, make it stick and provide an environment that will help athletes success even if your back is turned.

Misunderstanding the “Look Up” Cue

The final issue that causes deadlift hiccups is the misunderstanding of the common cue, “Look up!” Personally, I don’t like the cue and don’t use it. I think it misleads our athletes into confusing eye-focus with neck position.

There is actually nothing wrong with looking up, with your eyeballs, during a deadlift. But extreme extension of the neck during a deadlift is not beneficial. Many times, athletes default to that neck extension when the cue is used, rather than actually focusing upwards with the eyes.

The key word here is extreme. I don’t want to come off as one of these overly-cautious anti-extension-everything coaches. The spine has natural curvature that I believe should be utilized. I’m talking about the extreme over-extension of the neck that makes the scalenes light up like a Christmas tree and every vein in your neck come close to exploding. You’ve seen it. It looks painful. It is painful.

In this position it’s definitely tougher to maintain abdominal pressure and bracing, which is key for a deadlift. It also may be a challenge to maintain glute and hamstring tension due to the overactivity in the neck extensors.

On the flipside, you don’t want to overcorrect and end up in a forward head posture with rolling forward of the shoulders. People will say to keep a “neutral” spine, but the word neutral is a moving target. Neutral is a rabbit hole.

The bottom line is that I believe the “Look up” cue must be more deeply explain. If it sticks for the athlete, that’s fine. But if it creates a bad habit up cranking on the neck during heavy lifting, I’d try your luck with a different cue. Many times, simply putting an athlete’s head exactly where you want it and asking them how it feels is the best way to find the perfect head position. If it’s comfortable and doesn’t put them in danger, roll with it.

Subscribe to our blog

Subscribe to receive the latest blog posts to your inbox every week.

Related posts

Jumping to Conclusions: Workout Selection Based on 1 Simple Test

4 Physical Elements Of Developing Sports Performance