Grace Stiles (coach.grace27) brings experience as a Strength & Conditioning Coach to her role as an Assistant Soccer Coach at Marywood University. She is also the Head of Marketing at TeamBuildr.

I have had the opportunity to play soccer in college at the DII level and semi-professionally for 2 years. I have worked as a strength coach for a DIII men’s soccer program and am now an assistant coach and strength coach for a DIII women’s program. With that being said, I have been through my fair share of preseason training sessions and fitness tests.

“The Miler”

If you have ever played soccer, you have probably experienced a fitness test involving a continuous run of at least 1 to 2 miles. Imagine a sticky, August morning on the first day of two-a-days, and you and your team have to run “The Mile.” You are nervous, but feel prepared as you have been steadily running miles all summer. The test begins and your feet rhythmically strike the ground as you glide across the track. Finally, lap four is complete. You immediately place your hands on your knees to catch your breath and are relieved that it’s over. You pass the test under the required time limit, and now you’re looking forward to this evening’s training session because you actually get to touch a soccer ball!

During the evening session, you scrimmage full field, but you feel out-of-shape. How can this be? You ran in the grueling heat all summer long and even passed your fitness test. I, and many of my teammates, have experienced this sensation. We used to shrug it off because it was such a common occurrence following the summer break. We would say “running in the summer just isn’t the same as playing.” We hit the nail on the head without even knowing it. Yet, we would continue to train in the same manner and not question our training methods. I am not saying that long runs have zero transfer to the game of soccer, but I am saying that there are more effective ways of conditioning for the beautiful game. Soccer players do not continuously run 1-mile straight in a game-- so why would we train and test that way?

Energy System Development

Soccer games consist of a conglomeration of high-intensity sprints and low-intensity walks or jogs. When a soccer player does sprint, a majority of the time, it is only for 10-20 yards. In 2008, a study was conducted that analyzed movement patterns of Elite female soccer players within competition. Each player averaged 4 seconds of high-intensity activity followed by 44-64 seconds of low-intensity activity (Gabbett & Mulvey, 2008). However, it is common to find coaches administering fitness tests that involve long distances or 100+ yard shuttles.

Throughout a training session or game, a soccer player will tap into both the anaerobic and aerobic energy systems. As we know, the energy system used depends on the intensity and duration of that movement or exercise. The more intense the movement, the more dependent on the anaerobic energy system because it can provide energy quickly without oxygen present. Movements such as a quick sprint down the sideline, a goalie diving for a save, or a midfielder jumping to win a header are all high-intensity movements that depend on the anaerobic energy system. Energy for jogging up the field or for walking backward while the ball is out-of-bounds will largely be provided by the aerobic energy system.

Since soccer predominantly consists of aerobic activity, training the anaerobic energy system gets neglected. In all honesty, it can be very challenging to get a sport coach to understand why we are doing max-effort sprints with long amounts of rest in between. Most of the time, their instinct is to demand as little rest as possible. Even though the duration of high-intensity exercise within a game is small, these moments are what define the outcome of the game. A 2012 study analyzed the influence of speed and power movements in 360 goal-scoring situations in professional German League soccer. 83% of goals were preceded by at least one powerful action (defined as a straight sprint, change-in-direction sprint, jump, or a combination) from either the scoring or the assisting player. 45% of actions from the scoring players were straight sprints which transpired to be the most frequent action in goal situations (Faude, et al., 2012). Game-defining moments are composed of mainly speed and power actions which are greatly impacted by developing anaerobic adaptations.

Training The Anaerobic SystemThe anaerobic system includes the ATP-PC system and Anaerobic Glycolysis system. These systems are what fuel high-intensity exercises. Training these energy systems is important for all soccer players, but should be the primary focus for Goalkeepers. The ATP-PC system can be trained through max-effort speed drills with long rest periods. This not only includes linear sprints but also multi-directional and curved sprints. It can also be trained through plyometric exercises or power exercises such as broad jumps or med ball slams. The Anaerobic Glycolysis system provides energy for longer-lasting (10 seconds to 2 minutes) high-intensity bouts within a training session or game. The methods you choose to train the anaerobic system are dependent on athlete experience and progressions implemented so far.

Anaerobic Testing For Soccer Players

As a soccer player, I was never tested on an anaerobic component other than 1RM testing. In addition to 1RM testing, soccer players should be evaluated in sprint tests like the 10-yard dash and 5-10-5.

- 10-Yard Dash

The 10-yard dash is a simple way to measure linear speed and acceleration efficiency. Not only is it easy to set up, but it is also fun for athletes!

- 5-10-5

Otherwise known as pro-agility, this drill is a great reflection of change-of-direction and lateral speed.

- Goalkeeper Fitness Testing

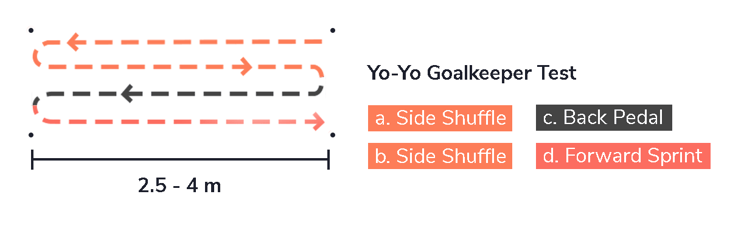

Most sport coaches will have Goalkeepers complete the same fitness test as field players, but lower the standard. This is easier than setting up a different test, but not as effective. The anaerobic system is the primary energy source for Goalkeepers so that is what they should be tested on. In addition to the 10-yard dash and 5-10-5, Goalkeepers should complete a variation of the Yo-Yo Test for Goalkeepers. This test consists of varying types of movement including side shuffles, forward runs, and backpedals across short distances.

The Aerobic system provides most energy for low-intensity movements or after 2 minutes of activity. I am not saying there is one correct fitness drill or test, but I believe that some conditioning drills are more practical than others. It is time to move on from old school, long-distance runs that your coach made you do in high school. I believe soccer conditioning drills should include these three components to be as game-like as possible:

- High-intensity sprints

- Low-intensity recovery bouts

- Change of direction

Aerobic Testing For Soccer Players

Fitness tests are overrated, but they can be a useful way to objectively evaluate fitness levels and to keep athletes accountable. The most “game-like” fitness tests are the ones that include high-intensity, low-intensity, and change of direction as mentioned before.

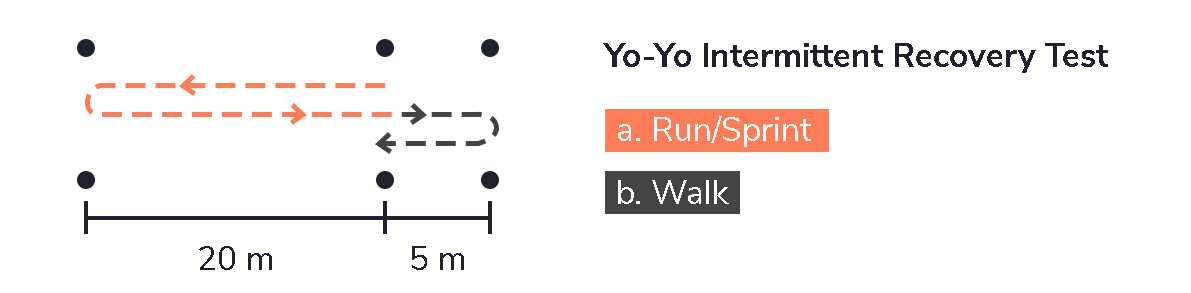

- Yo-Yo Intermittent Test

The Yo-Yo test is a beep test variation (I am sure this is a triggering thought for some of you) that takes a step further toward soccer-specific demands. This test is a maximal aerobic endurance fitness test that involves a high-intensity run, multiple changes of direction, and a low-intensity walking portion. It may be absurd to think that there is walking in a fitness test, but that replicates the sport the best. One study assessed the physical fitness, match performance, and development of fatigue during competitive matches for 18 top-class and 24 moderate professional soccer players. During competition, the top-class players performed 28 and 58% more high-intensity running and sprinting than the moderate players. Additionally, the top class players performed 11% better on the Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test (Mohr, et al., 2003).

- 15-Minute Fartlek Test

The word Fartlek means “speed play” and this is one of the best types of training for soccer athletes. This is a fitness test that I have created myself, where the goal of the test is to cover the greatest distance possible in 15 minutes (can be done for a shorter amount of time). This test continuously rotates through a 40-second jog, a 10-second max-effort sprint, and a 10-second walk. You complete that sequence 15 times and measure the distance covered. This test can be done on a track or a field, but there are pros and cons to both:

- Easier to incorporate change of direction

- Athletes are running on the same surface that they play on

- Harder to measure the distance covered (without GPS tracking)

- Easier to measure the distance covered (without GPS tracking)

- No change of direction element

This test is more convenient for athletes to replicate when they are training on their own rather than setting up cones and the audio for the Yo-Yo test.

Conclusion

The most effective way to train for soccer is by incorporating fitness tests and drills that target both anaerobic and aerobic energy systems. No energy system should be neglected, and it is critical to communicate this with sport coaches. Ultimately, it is the sport coach's decision on what fitness tests are administered but focus on the parameters that you can control.

References

Gabbett, Tim J, and Mike J Mulvey. “Time-Motion Analysis of Small-Sided Training Games and Competition in Elite Women Soccer Players.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 22, no. 2, 2008, pp. 543–552., https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e3181635597.

MOHR, MAGNI, et al. “Match Performance of High-Standard Soccer Players with Special Reference to Development of Fatigue.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 21, no. 7, 2003, pp. 519–528., https://doi.org/10.1080/0264041031000071182.

Faude, Oliver, et al. “Straight Sprinting Is the Most Frequent Action in Goal Situations in Professional Football.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 30, no. 7, 2012, pp. 625–631., https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.665940.Subscribe to our blog

Subscribe to receive the latest blog posts to your inbox every week.

Related posts

Aerobic Conditioning for the Tactical Athlete

My Players Failed the Conditioning Test, What's Next?