Deceleration Training: Building Better Brakes

Deceleration is an important topic in strength and conditioning due to the primary focus on preserving athlete health for improved performance. Building deceleration skills can unlock an athlete’s true potential not only for improved athletic performance and eccentric loading capacity but also for the development of a greater resilience to injury.

Picture this: you’re back in high school. You and your teammates are on the line preparing for the next round of sprints. Your coach yells out “Sprint fast off the line”! He blows the whistle, and everyone shoots out in front explosively and darts forward like speeding bullets. Now, that’s an expression of acceleration.

Acceleration is the exact opposite of deceleration. If acceleration comes down to your ability to speed up fast, then deceleration represents your ability to slow down fast. Conceptually, slowing down fast is a challenging idea for people to grasp. However, when we consider eccentric braking forces and your ability to change directions efficiently, it all starts to make sense.

Deceleration ability incorporates force absorption, which is a fancy term for your body’s ability to accept load. This can occur during a variety of athletic situations in sports:

- Change of direction while running forward (i.e., an American football player or Rugby player planting hard into the ground to juke out the defender and avoid being tackled)

- Pumping the brakes aggressively to completely turn around and run in the other direction (i.e., a turnover of possession in basketball where you’re focused on getting back on defense)

- Upon impact from either landing (i.e., coming back down to the floor after a spike in volleyball) or through contact with another player (i.e., fighting off a defender in soccer with your body to win the head ball off a corner kick)

Possessing the skill of deceleration in spades is a key characteristic of athleticism. Taking a multi-pronged approach in the weight room and on the field/court is how you can improve your deceleration ability. The weight room opens the door for plyometrics and strength training while the field/court opens the door for speed and agility training. Both environments matter and both should be trained appropriately.

Underlying Qualities Athletes Should Possess Before Continuing

Key qualities that contribute to your ability to decelerate efficiently and effectively center around lower body durability, body control, and braking forces.

Lower body durability consists of incorporating direct loading exercises to strengthen one area of the body. For example, you can directly load the calf region in your lower leg through either standing or seated heel raises. You could also perform single-leg exercises like split squats or 1-leg RDLs - these would represent indirect loading strategies. The key here is to directly load the targeted area.

Common sites in the lower body that often fall prey to athletic injuries are the calf region, the knee region, the hamstring region, the groin region, and lastly, the hip flexor region. Providing direct loading exercises in these 5 areas will help to strengthen not only the associated muscles but also the associated support structures (i.e., tendons, ligaments, etc.). The calf region is easily one of if not the, most important lower body area since it includes the soleus muscle. The soleus muscle has a large physiologic cross-sectional area (PSCA), which ultimately means that it was designed to produce massive amounts of force as it works in tandem with the Achilles tendon during jumping and landing activities.

Soleus direct loading example:

The ability to control your body in space is a basic way to view athleticism. Body control, therefore, is paramount for improving deceleration ability. You can achieve this through a variety of exercises that primarily focus on yielding isometrics and overcoming isometrics.

Yielding isometrics represent a less intense version of isometric training where the focus is on maintaining a still position while holding a weight or object in place to prevent it from giving in to the forces of gravity. A simple example is a wall sit where the athlete is holding one dumbbell with both hands in front of the chest in the Goblet position.

Yielding isometric example:

Overcoming isometrics, on the other hand, represents a more intense version where the focus is on exerting maximal effort and force to attempt to move an immovable object. A great example of this is when an athlete performs the isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP).

Overcoming isometric example:

Athletes stop on a dime and change directions in nearly every sport where braking forces are applied in these types of scenarios. A lot of this can be attributed to these athletes having mastered the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) and simply possessing elite-level athleticism. However, it would be wise also to train these qualities to ensure that we’re turning over every stone. The ability to control braking forces efficiently and effectively comes down to your ability to control the eccentric phase of movements.

The eccentric phase is often referred to as the lowering phase of a movement where there is a lengthening under load. We can incorporate eccentric training through a variety of exercises to support improved braking forces. One example that comes to mind is when an athlete is performing a split squat. You could spend a longer amount of time in the eccentric phase of the split squat. This might look like 5 seconds lowering down eccentrically, holding for 1 second in the bottom position isometrically, and finally, ascending to the top for a 3-second count concentrically. On the other hand, you could instead perform just the eccentric phase of the split squat, and then skip the isometric and concentric phases. This eccentric-only version will be much more challenging.

Eccentric example:

Weight Room: Programming Considerations, Progressions, and Regressions

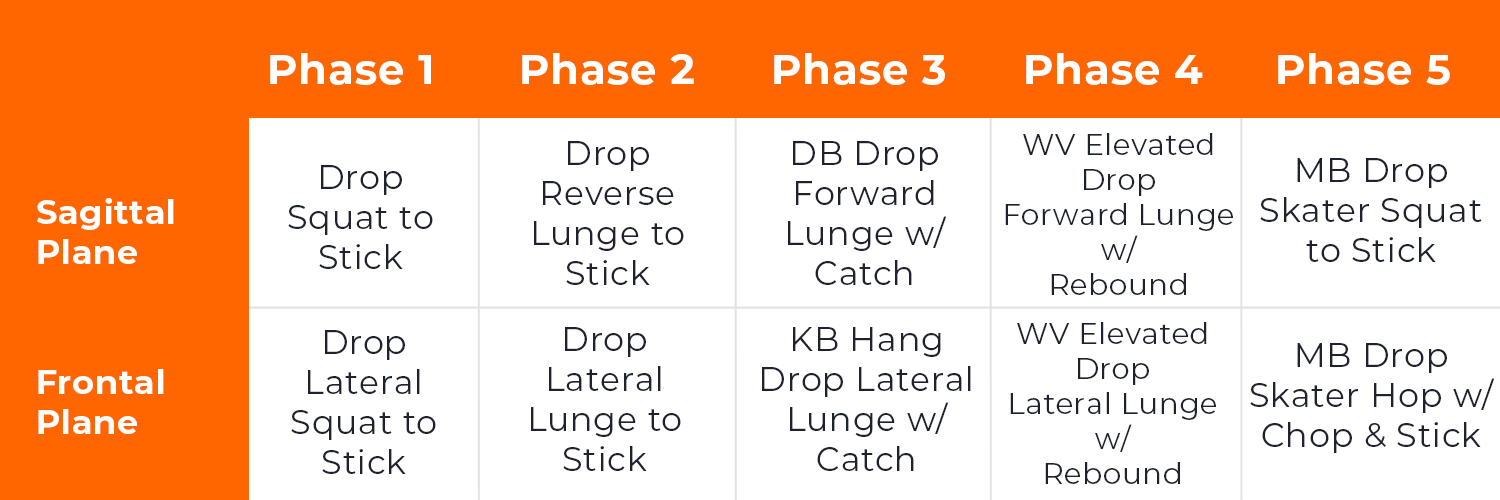

Whether you’re in the weight room or on the field/court, it’s important to respect and incorporate exercises in all 3 planes of motion: sagittal plane, frontal plane, and transverse plane. The sagittal plane consists of forward and reverse movements, the frontal plane consists of side-to-side and lateral movements, and finally, the transverse plane consists of rotation and twisting movements. The sagittal and frontal planes are much easier to develop and would be recommended first. Once you’ve mastered deceleration exercises in those planes, I’d suggest to then move into the transverse plane through combination movements.

The primary goals of building deceleration ability in the weight room are to help athletes feel the ground underneath them, improve their ability to control their body and self-organize, and most importantly, to land with intent and purpose. It’s important to remember that sports occur at high speeds, at various angles, and in violent/aggressive manners. At some point, what we do in the weight room needs to be advanced enough to be able to mimic the environments seen in sports for true transfer to occur. Over time, the objective is to gradually increase eccentric braking forces to enhance the intensity of the deceleration component during each phase of training.

With that in mind, here are the programming considerations in the weight room:

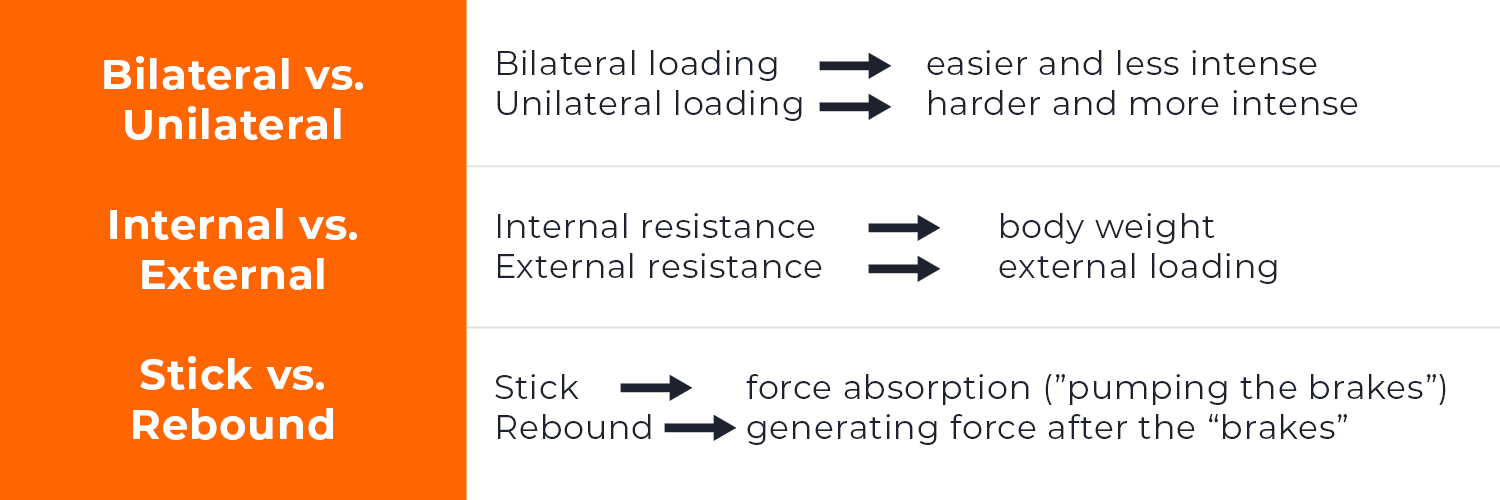

When it comes down to loading, you can opt to use a bilateral (easier and less intense) or unilateral (harder and more intense) approach. For resistance, you can start with internal resistance (body weight) and then advance to using external resistance (external loading). Lastly, the first step is to master the ability to stick your landing (“pump the brakes”). In doing so, this will improve your ability to absorb force. Then, when you’re ready to advance, you can add in the rebound, which demonstrates your ability to generate force directly after pumping the brakes. Here’s a visual example of this below to bring it to life:

Band Resisted Drop Forward Lunge w/ Rebound

When it comes down to exercise selection, there’s a ton of variety. It truly doesn’t matter which exercises you choose to implement. Rather, what’s more important is that you respect the planes of motion and adhere to the programming considerations. From there, you can simply fill the buckets by selecting exercises that you see fit.

For starters, here’s a simple table to follow that breaks down sagittal plane and frontal plane deceleration exercises in the weight room throughout 5 training phases:

Here’s what each of these exercises looks like in the sagittal plane:

Drop Squat to Stick

Drop Reverse Lunge to Stick

DB Drop Forward Lunge w/ Catch

WV Elevated Drop Forward Lunge w/ Rebound

Medicine Ball Drop Skater Squat to Stick

Now, here’s what each of these exercises looks like in the sagittal plane:

Drop Lateral Squat to Stick

Drop Lateral Lunge to Stick

KB Hang Drop Lateral Lunge w/ Catch

WV Elevated Drop Lateral Lunge w/ Rebound

Medicine Ball Skater Hop w/ Chop & Stick

Field/Court: Programming Considerations, Progressions and Regressions

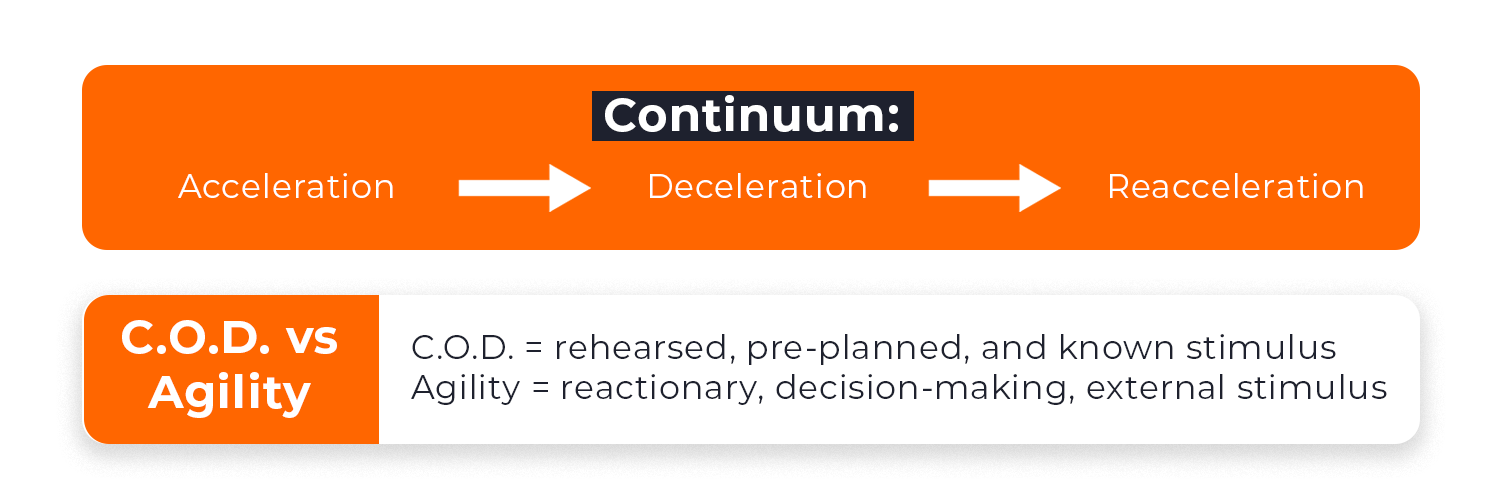

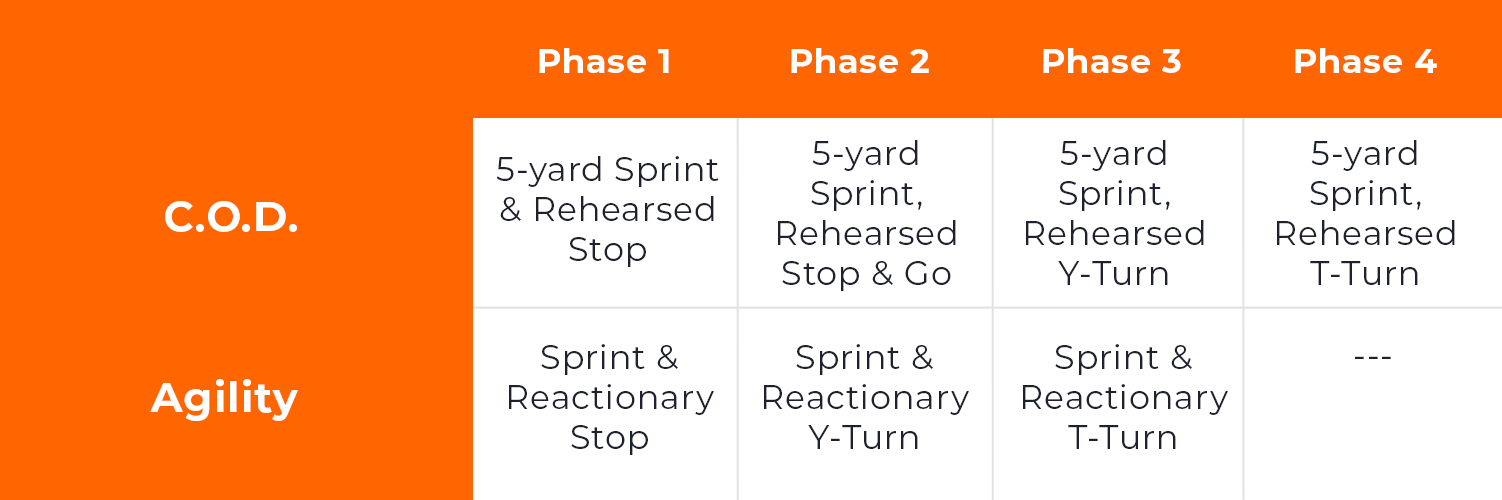

Once we move out of the weight room and onto the field/court, we realize that there’s a continuum at play that we must appreciate. This continuum harnesses the athlete’s ability to accelerate (speed up), decelerate (slow down), and then reaccelerate (speed up again, likely in a different direction). Within this continuum, we can dig deeper to find Change of Direction (C.o.D.) outputs and agility outputs. There is a difference between the two, which helps to understand how to create exercise progressions from phase to phase with your athletes. However, C.o.D. and agility are often intertwined and overlap in many ways.

Here are programming considerations on the field/court:

Starting with C.o.D. exercises allows the athlete to have a basic point of entry. Rehearse, pre-plan, and provide a known stimulus. That way, the athlete will be on the fast track to success when it comes to mastering the learning curve. Once the athlete is ready to advance, you can then begin dialing up the intensity by incorporating true agility exercises that focus on decision-making skills where a reaction is required in response to an unplanned external stimulus.

Let’s put everything together so that you can begin using deceleration exercises on the field/court course of 4 training phases:

Here’s what each of these exercises looks like for C.o.D.:

5-Yard Sprint & Rehearsed Stop

5-Yard Sprint, Rehearsed Stop & Go

5-Yard Sprint & Rehearsed Y-Turn

5-Yard Sprint & Rehearsed T-Turn

And lastly, here’s what each of these exercises looks like for agility:

Sprint & Reactionary Stop

Sprint & Reactionary Y-Turn

Sprint & Reactionary T-Turn

Conclusion

Deceleration is a key characteristic of athleticism and should be trained during weight room activities (plyometrics and strength training) and field/court activities (speed and agility training).

Athletes should possess lower body durability via direct loading strategies, body control via isometric loading, and braking forces via eccentric loading before continuing.

Weight room considerations for deceleration training include an appreciation for all planes of motion and building the athlete up in a progressive manner that eventually mimics the environments seen in sports.

Similar to the weight room, field/court considerations for deceleration training include an appreciation for all planes of motion, in addition to challenging the athlete in a progressive manner that eventually mimics game-like environments.

Subscribe to our blog

Subscribe to receive the latest blog posts to your inbox every week.

Related posts

Systematic Approach to Movement Preparation

Prevent & Preserve: A Guide to Low Back Training