Why You Should Be Doing Isometric Training At Home

If you’re like myself, or like anyone else reading this article right now, you’re most likely quarantined at home with no access to a gym and limited to cans of beans, cases of water, and your own body weight as your only means of “equipment.” Luckily, coaches and physical educators have stepped up big time with creative – sometimes obscure – methods of training to keep everyone moving.

Unfortunately, one method of training hasn’t been receiving as much love as the others. It’s not flashy – which is probably why you don’t see it on social media - and it certainly isn’t easy, but it may be the most simple and effective way to train when resources are scarce: isometrics. Isometric training can provide a safe and effective opportunity for progress and adaptation to occur when implemented properly.

DEFINING ISOMETRICS

Isometrics are one of three different muscle actions; the other two being eccentric (lowering) and concentric (lifting) contractions. From an outsider point of view, isometrics can be characterized by a lack of movement or a static state. However, when viewed from an internal point of view, isometrics are continual tiny contractions happening deep inside the muscle.

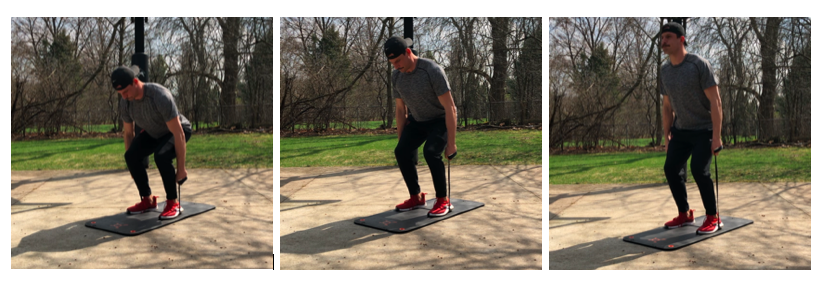

An isometric contraction occurs when the force you’re exerting equals the force of the load, or in some cases, when the load is greater than the force you’re exerting on it. This can be visualized when you must hold an object above your head in attempt to keep it from falling, or if you try to pull a car with the parking brake still on. The former of these two examples can be considered a yielding isometric, while the latter is considered an overcoming isometric. Understanding the difference between these two methods is important when it comes to applying isometrics.

Yielding vs. Overcoming

Yielding isometrics is the holding of a weight or object to prevent it from succumbing to forces of gravity. Think holding a plank or staying seated in a wall sit. You are resisting movement. Yielding isometrics can best be applied when attempting to train a muscle to become less resistant to fatigue, increasing muscle mass, or trying to teach muscular control.

Overcoming isometrics is an attempt to move an immovable object by pushing or pulling on it. Think of trying to pull a tree stump out of the ground; it just isn’t happening. Consider using overcoming isometrics to get increases in strength, break through a sticking-point, or potentiate more dynamic movements.

Image 1. (Left) yielding isometric. (Right) overcoming isometric with strap.

Isolated vs. Complex

It’s also important to note the difference between an isolated isometric and a complex isometric. When a single joint is being acted upon it can be considered an isolated isometric (ex. isometric bicep curl). When multiple joints, and thus more musculature, are called into action it is a complex isometric (ex. isometric split squat). It is important to differentiate between the two as they both will utilize a varying degree of energy, with complex requiring more in the majority of scenarios.

BENEFITS OF ISOMETRIC TRAINING

Isometrics can offer a wide array of performance benefits, but my focus will be increasing strength and muscle mass.These findings have been well researched but are often times forgotten. This article’s intent is to bring to light those isomeric training benefits and offer an effective way to implement for yourself and your population.

Isometrics for Strength

Research done in 2001 found that during an isometric contraction there is ~5% more muscle fiber activation than when compared to eccentric and concentric contraction of that same muscle. This increased ability to recruit more muscle fibers can improve the neural drive when performing contractions, thus leading to an increase in strength over time.

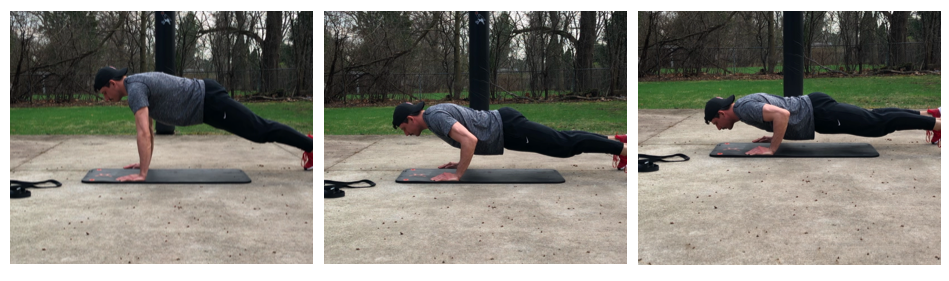

However, there are two caveats to increasing strength via isometric contractions. The first is that this can only generally happen while utilizing overcoming isometrics. Performing max efforts against an immovable object for roughly three to six seconds is the best way to tap into this potential. The three seconds allows enough time for a “ramping up” of the movement being performed. The second is that the strength increase only happens at the joint angle that the contraction is being performed at. There is evidence to suggest that the strength gains can also be realized at a +/- 20-degree range of that angle, but it is best to train varying joint angles in order to maximize the effect (see Images 2 & 3.).

Image 2. Varying angles of a deadlift overcoming isometric with strap.

Image 3. Varying angles of a push-up yielding isometric.

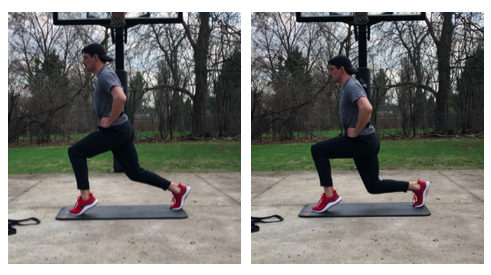

Isometrics for Anatomical Adaptations

Near the start of every off-season training program I have become accustomed to including a ton of isometrics, specifically yielding isometrics. After nearly eight months of running and jumping every day, my athletes’ bodies have neared their breaking point. Yielding isometrics offers a chance to rebuild tendon structures and quickly accumulate muscle without significant dynamic movement - something I try to give their bodies a break from at the start of the off-season. Starting with several sets of 20 seconds and eventually progressing to 60 seconds stimulates the hypertrophy response. I have also found anecdotal evidence that this is a great tool for gaining muscular control in specific positions, like the bottom of a push-up or the split squat which may help a novice lifter or someone rehabbing an injury.

Image 4. Split-squat yielding isometrics at varying angles with plantar-flexion.

HOW TO IMPLEMENT ISOMETRIC TRAINING DURING A QUARANTINE

In this current situation, yielding isometrics are generally easier to implement than overcoming isometrics. For most training protocols, all you need is your bodyweight. I like to pair up a dynamic exercise with an isometric in a superset. For example, perform a set of Step-Back Lunges then pair that with a Low Split-Squat Yielding Isometric to pre-fatigue the working muscles and build additional muscle mass.

Here are several programming examples of yielding isometrics:

| 1a. Step-Back Lunge | 3 x 10 each leg |

| 1b. Low Split-Squat Yield Iso | 3 x 20sec. each leg |

| 1c. Push Up | 3 x 10-20 |

| 1d. ½ Push-up Yield Iso | 3 x 20sec. |

| 1e. Bicep Curl | 3 x 15 |

| 1f. 90-degree Bicep Curl Yield Iso | 3 x 20sec. |

| 2a. Single Leg Glute Bridge | 3 x 10 each leg |

| 2b. Single Leg Glute Bridge Yield Iso | 3 x 20sec. each leg |

| 2c. Prone T-Raises | 3 x 10 |

| 2d. Prone T Raise Yield Iso | 3 x 20sec. |

| 2e. Standing Calf Raises | 3 x 15 |

| 2f. Calf Raise Yield Iso | 3 x 2osec. |

Image 5. Shoulder Y, T, W, A, L yielding isometrics. (Kneeling position for demonstration, best performed in prone position).

Overcoming isometrics may require a bit more creativity. My favorite tool for performing overcoming isometrics is six to eight feet of strong nylon strap; two belts strapped together will also suffice. You can also utilize a sturdy wall or a parked car. The goal here is to express force with as much effort as possible. It is the intent in performing overcoming isometrics that make them beneficial. These too can also be paired up with a dynamic exercise, with the isometric being a potentiator for the dynamic movement. For example, perform a Bilateral Overcoming Iso Deadlift then perform Max Counter Movement Jumps.

Here are several programming examples of overcoming isometrics:

| 1a. Overcoming Iso Deadlift | 5 x 3-6sec. |

| 1b. Counter Movement Jump | 5 x 3 |

| 2a. Lateral SL Overcoming Iso | 5 x 3-6sec. |

| 2b. Skater Hops | 5 x 3 each side |

| 3a. Standing Wall Pushed | 5 x 3-6sec. |

| 3b. Elevated Plyo Push-Up | 5 x 3 |

Image 6. Lateral single leg overcoming isometric.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

When communicating with these exercises with athletes, it’s always good practice to provide an analogy that carries over to sport. For my basketball athletes, letting them know the role isometric contractions play in their jump shot (via the stretch-shortening cycle) or when their battling for position in the paint with their opponent always seems to create for more buy-in and adherence to the methods.

Like always, it is important to ensure the safety of these methods and exercises. Program prudently to start, then begin to add more in as you see fit.

References

- Balbault N, Pousson M, Ballay Y, Van Hoecke J. Activation of human quadriceps femoris during isometric, concentric, and eccentric contractions. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91(6), 2628-34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11717228. Accessed March 30, 2020.

Subscribe to our blog

Subscribe to receive the latest blog posts to your inbox every week.

Related posts

The Top 5 Career Killers for Coaches

Conditioning is as Simple as Walking, Jogging, Running, & Sprinting