Sense-Making in Performance Training: Weighing Novelty and Structure

Physical preparation training is extremely diverse in the approaches that can be taken. There are countless models, methods, and means of training an individual or group. The creativity that can be exercised (pun intended) is endless. There are so many options that it can become paralyzing. It’s important to make sense of our environment and then act appropriately in it. The aim is to simplify things down to a level that allows us to navigate the world efficiently, but not so simply that the map looks nothing like the territory.

Debates on volume, intensity, and frequency have been had ad nauseam over the years, so I won’t rehash those things. Instead, I’ll focus on two different trains of thought that influence all models of performance. In broad, overarching terms, periodization methods tend to have elements of both planned (top-down) and emergent (bottom-up) prescription. This can be framed into objective search and non-objective search. These terms were popularized by Kenneth O. Stanley and Joel Lehman when describing different algorithms in their artificial intelligence research and in their book: Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned.

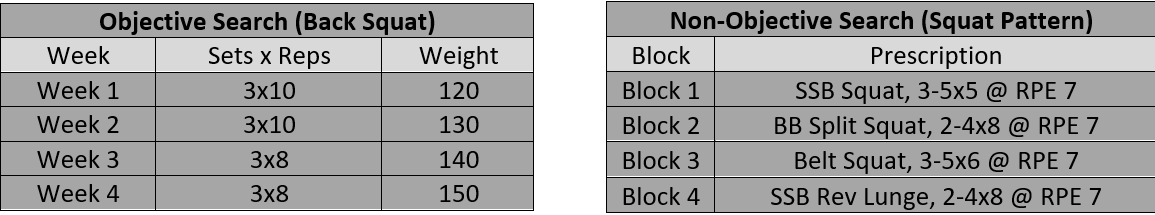

Objective searches are your classic periodization schemes; linear, undulating, block, etc. Objective search is characterized by a known objective and known steps do get to the objective. You have a goal in mind, and you implement the exercises, loads, and progressions to get there. Weeks are planned in advance. You know the weights you’ll lift, days you’ll train, and distances you’ll run along with all the other parameters of training. Newbie trainees, those that come off of training breaks, and those going through new training blocks respond well from simple progressions.

Non-objective search is a bit different. In terms of periodization strategies, it has more in common with Bondarchuk’s system, Mike Tuchscherer’s Emergent Strategies, or Mladen Jovanovic’s Agile Periodization. These systems rely heavily on the influence that emergent information has on training. Non-objective search revolves around looking for novel opportunities and results. It’s like a treasure hunt. Keep turning over stones until you find something interesting or valuable. This becomes important when dealing with someone that can’t break through a plateau, is of elite training status, or someone who has chronic pain/injury. If best practice isn’t working, you have to look for something different.

These two types of searches require different modes of thought; objective search being mostly deductive and non-objective search being more inductive. Neither is good or bad. Like most things, it’s figuring out which is appropriate and when. How do we know when to switch modes of thought? Should we base it on population or training age or training constraints? This may be a good start, but many times it ends up being as restrictive and dogmatic as arbitrarily choosing a scheme. We need a map. Something that tells us when it’s time to switch strategies. That’s where sense-making comes in.

A Sense-Making Framework

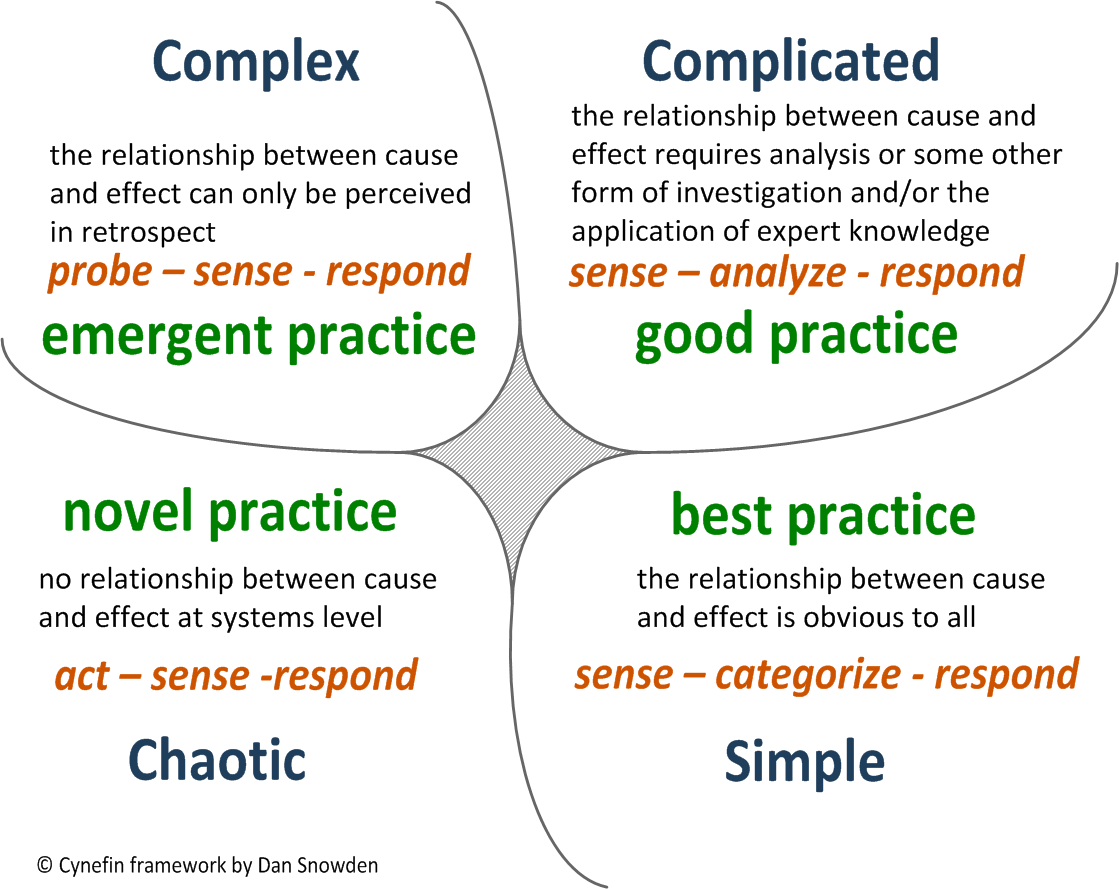

The Cynefin framework was developed by Dave Snowden to help people make better decisions. Cynefin is a Welsh word that means “habitat”. When you view these four areas as domains that we “inhabit” at any given moment, the namesake makes sense (pun totally intended…I’m sorry, I’ll stop). This graph may seem esoteric and vague, but that’s because it is. Once we add in some examples, hopefully things will become a bit clearer. We’ll go through each domain and provide clarity.

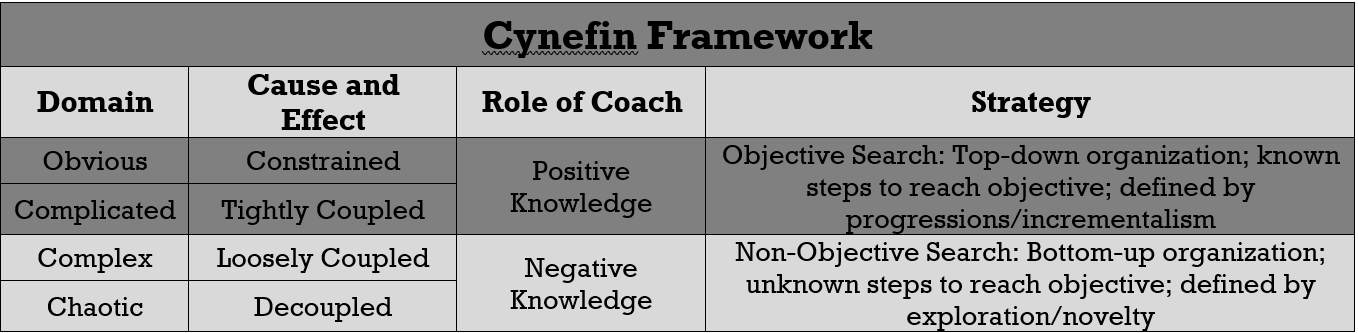

Although it becomes a little messy, I tend to lump the simple and complicated domains together and join the complex and chaotic domains together. This forms our two broad approaches of objective and non-objective search.

The Domains

The simple and complicated domains are characterized mainly by cause and effect having a solid relationship. Since this relationship is strong, objective search is applicable. When there is a good relationship between cause and effect, a coach can use positive knowledge (the knowledge of what to do) as a guide. This puts the coach in a role where they are in control of parameters and prescription of training. They can focus most of their effort on progressions and training trends.

On the other hand, the complex and chaotic domains have a very loosely coupled or decoupled relationship. Because of the lack of connection between cause and effect, non-objective search is more applicable. Positive knowledge isn’t as useful since it isn’t clear as to how the training is producing certain outputs. This is where the role of the coach transitions into using negative knowledge (the knowledge of what not to do). Here it’s more important to know the potential downsides and pitfalls of the training, and to act as a guide through novel experiences.

Criteria For Determining Type of Search

Knowing which strategy to use – objective or non-objective search, top-down or bottom-up – can seem like a daunting task, but in reality, finding an athlete’s current domain is fairly simple. There are three main categories that I attempt to understand when assessing an athlete.

- Long-term Training Status (Chronic)- Does the athlete have ten years of performance training under their belt or have they never touched a barbell? Obviously (hence the domain), the latter can respond more favorably to longer blocks of small increases in training load. Novelty can be low for new trainees and high for older athletes. The nice thing about novel stimuli for older athletes is that the training load can be relatively low (because it’s novel) while still getting a reasonable training effect. Most experienced athletes will get to the point where their usual training yields extremely diminished returns. Novelty, although scary, is useful for them. This isn’t to say you won’t implement progressions for experienced athletes, it’s just that you will spend more time looking for novelty than with a less experienced athlete.

- Short-term Training Status (Acute)- Knowing what the athlete has done in the recent past goes a long way. If they are deep into a training block, there may be some need for novelty. If they are just starting a new block of training or are coming off a layoff, progress and watch trends. The short-term training status should give you a “feel” for how they should respond to training. It’s not always true, but it usually is. Established training wisdom is a good reference. If a new trainee has been doing the same program for twelve weeks, you might get the feeling that they need a change. They probably do.

- Training Result- Out of the three criteria, this one carries the most weight. Both of the previous criteria carry a boatload of assumptions. Although it’s tough to assign meaning or causality, there is less subjectivity in raw data. Training results are a representation of what “is” instead of “ought” to be. I tend to separate training results into two categories; responsiveness and reactiveness.

- Responsiveness- This is the positive effect from training. Any of the performance metrics you’re currently tracking would fit into this category; 1RMs, vertical jump, sprint/agility times, etc. Seeing the trends of the weekly training outputs you’re recording will give you an idea if your athletes are gaining fitness. This takes patience and some experience when looking at training responses. It’s also tricky to know when to switch gears and introduce novelty again. With newer trainees, you almost have to hold back progress at some points (soon to ripe is soon to rot), and with more experienced athletes, even small signs of progress are worth their weight in gold. Although you want small progress from both groups, it’s most likely that the prescription changes are smaller for the less experienced and larger for the more experienced. If both of these strategies produce similar responses, you’re getting close to the answer.

- Reactiveness- This is the negative effect from training. It’s entirely possible and even probable that most athletes will need to accumulate some level of acute and chronic fatigue in order to see progress. HRV measurements, subjective questionnaires, Omegawave readings, etc. all communicate an athlete’s fatigue in some sense. These tests will require some finesse though, as it’s unclear as to how much fatigue someone should have. We know that it isn’t zero and it isn’t the maximum amount of fatigue possible. It lies somewhere in between. Look at performance and look at fatigue. At times when performance is trending up, take note of the fatigue measurements. The global fatigue that’s associated with improved performance will be stable over moderate time scales (a couple years at least). Besides all of the other factors you would adjust in training, replicating similar fatigue levels could prove useful.

Above are some concrete examples of the different types of search.

In Summary

In objective search, the coach tightly controls prescription, implements known best/good practice with progressions and incremental increases in workload. This tight control of prescription produces a significant and reliable training response. Patience is the name of the game. Most coaches are masters at this craft. Very little analysis and novelty needed. Just follow the playbook. The coach can rinse and repeat old reliable training blocks for years and get great results.

In non-objective search, the coach is a treasure hunter. They are looking for something interesting. They act as a guide for the athlete to take themselves through the training experience rather than imposing the training plan from the top down. Once they have explored and found something promising, they exploit that thing to see how much juice they can squeeze out of it. The landscape can be chaotic, and this is why the coach must have good intuition to be able to read training responses (sensing is the second step in this domain, acting/probing the first) so they can appropriately adjust. Implement novelty, sense, adjust, repeat.

With each passing year, it seems like I have more questions and fewer answers. However, this simple model has helped me answer a few of the thousands of questions that I have. I hope it helps you, too.

Subscribe to our blog

Subscribe to receive the latest blog posts to your inbox every week.

Related posts

Cooks Before Chefs: 4 Steps to Teaching Young Coaches to Program

The Pitfalls of Autoregulation