From the Ground Up - The Benefits of Structured Exercise Progressions

Designing quality, targeted exercise programs is no easy task, involving careful consideration of a myriad of factors. There are the goals of the client or athlete, expectations of coaches and/ or parents, and building for long-term success. At the same time, we need to match the program to their current movement ability and exercise capacity, make sure they can perform at their potential each game or competition, and keep them engaged in their training.

Program design goes beyond the selection of exercises sessions across a block – it is about how well exercises and programs transition across blocks, and how they fit within the structure of the season and the athlete’s development plan, and their weekly performance. Which brings us to the purpose of this article - to get you thinking more deeply about exercise selection, enabling you to design better programs. Smart programming provides the platform for athlete AND coach to perform at their best.

First, let’s consider how ‘easy’ some common exercises really are? Think of the deadlift and squat; KB swing and BB rear foot elevated split squat; BB bench and shoulder press - elite athletes take time to learn and master them, and still make mistakes (otherwise they wouldn’t need coaches). Yet these same exercises are often the starting point for youth athletes, and mostly sedentary, ‘gen pop’ clients. Not only do elite athletes get better access to quality coaching, they often have much greater movement skills and body awareness (from here, I’ll use the terms client and athlete interchangeably).

By now, hopefully you’re thinking, ‘so, if elite athletes take time to learn and master these common exercises, why do we expect youth athletes or previously sedentary, ‘gen pop’ clients, to nail them so early? Unfortunately, the thought process seems to go more like this:

First session with a new client, let’s back squat; Athlete needs single leg strength, let’s Bulgarian Split Squat; Client wants a bigger chest, let’s BB bench press.

It’s not to say we can’t use these exercises straight away. However, considering even a ‘simple’ Bird Dog is frequently butchered, perhaps there is a smarter and easier way?

Programming this way is analogous to expecting to drive a race car before you’ve got your learner’s license - unless you’re Daniel Ricciardo, which you probably aren’t! Look around and you will see it occurring across a variety of settings – with athletes, general pop, and rehab, in professional sport and in private facilities, and especially on Instagram.

It shouldn’t be entirely surprising that we sometimes overshoot in our exercise selection- I know I’ve done it before. When we start programming for a new athlete, we often need to make educated guesses about their exercise capacity, and we can be wrong. Perhaps the athlete has embellished their experience, you’re a young coach still finding your feet, or the client didn’t tell you about that previous knee injury. Sometimes we simply make a mistake.

Which brings us to a solution. I believe we need to take a few steps back in our approach to exercise selection, so we can (eventually) take leaps forward. To do this, we first need to consider a few key points:

- Exercise selection must reflect the needs and demands of the athlete as they are NOW, not where we wish they were – or where THEY think they are (1).

- The levels we want or need the client to GET TO play an integral role in how we structure exercise progressions. This relates to the present and the future.

- Understand WHY we are selecting each exercise, and how it fits into the development and performance of the athlete.

- Build the exercises, as we build the athlete.

In other words, work from simple to complex - starting easy and gradually increasing skill and loading requirements. Utilising this strategy has many benefits - it increases likelihood of success for the client (1), makes it easier to align with current skill levels, and helps reduce coaching demands. Further, it makes each new exercise a transition rather than a totally new exercise – we progress the exercise by manipulating the implement, task outcome, adding small amounts of information, or change a cue (1,2). This ‘repetition without repetition’, (2) provides plentiful opportunities for ‘failing safely’ and developing error-detection abilities, and the ability to coach themselves and each other. This positive feedback loop keeps informing the athlete and coach and enables consistent improvement and success.

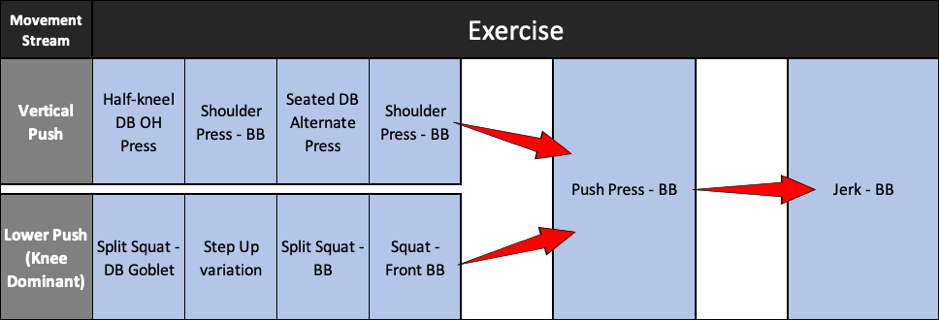

Using these considerations, let’s look at how we might progress a novice towards a barbell Jerk. To begin, can they control their own body weight and handle loads over head? As a novice, let’s assume they can’t. Next, is the jerk an exercise that will benefit them in the future? If they play a land-based sport, the answer is most likely, yes – but it’s not likely to be a priority at the moment (even if it was, improving their general strength would likely have much more immediate benefit), giving us time up our sleeves. Once we’ve decided it is an important exercise, we need to decide where it sits in their development plan (as it’s not related to performance, yet). This will be influenced by many things, including their sport, equipment available, and the skill of the athlete and coach (a good coach is comfortable admitting when they don’t have the capacity do something, which could be due to skills, logistics, time, etc).

The Jerk is an aggressive, total body lift with coordination, speed and stability demands, making it applicable to any sport that involves jumping, changing of direction, acceleration and deceleration, and particularly where contact or fighting for body position is involved. Anecdotally, there is also a tonne of confidence to be had from violently lifting and controlling a heavy load overhead. Personally, I think it has more utility than the other Olympic lifts and variations, able to be done just as effectively with light loads, KB’s or DB’s, and as single or double arm versions - the concentric dominance and small ROM of the jerk also make it applicable during competition periods.

Which brings us to the final consideration – building the exercise as we build the client. We could certainly teach the jerk straight up - but that would be coach intensive, likely a long process, and the light loads would mean low physical stimulus. Alternatively, we could start with split squat and overhead press variations as separate exercises and gradually increase the difficulty of each – allowing us to increase the strength, control, and skill repertoire of the client. The following figure provides an example of how such a strength training progression might look.

Structuring progressions in this way allows us to develop physical qualities while introducing and reinforcing the positions, postures, and cues required for more complex exercises. In relation to the push press and jerk, we have been building towards:

- Accepting load in a split stance and overhead position,

- Establishing a front rack position, initiating movement from the hips and ‘exploding’ off the floor to create bar momentum,

- Maintaining an upright trunk while holding a load overhead

The instructions for transitioning from the shoulder press and front squat are succinct and simple - ‘Dip, Explode, and Punch’ for the push press becomes ‘Punch and Split’ for the jerk (‘exploding’ has already been established). By making our instructions our cues, we can provide immediate feedback from anywhere in the gym – ‘Great punch’; ‘Faster split’; ‘Explode!’

The jerk is not an easy exercise to perform or coach – by chunking the teaching of it into easier exercises we only need a small amount of dedicated coaching to go from the push press to the jerk. Aside from reducing our coaching demands, we’ve increased the client’s chances of success and provided autonomy while mitigating many potential logistic issues along the way. Work smart, not hard.

Despite our best planning, last minute, individual changes to programs are often required, especially during hard training blocks and competitive periods. Perhaps training went for two hours instead of one, or the team ran more than expected on the weekend. Structured exercise progressions provide us with an excellent back up plan – all we need to do is drop back to the push press (removed the split stance) or go back even further to a shoulder press and front squat. The athletes have done them very recently, so the chance of DOMS is reduced, and the positions and postures are fresh in their mind.

As coaches we should be aiming to coach ‘no more than we must’, providing athletes with the right balance between challenge and likelihood of success (1). Further, we need to provide space for them to make mistakes, figure things out, and learn. Each of these goals is more difficult if we go straight to complex exercises or lose the ability to coach from a distance. Coaching efficiency is crucial when coaching groups or teams, but even for 1-on-1 sessions - why limit yourself to just one client every session, if you can coach two, three, or more. Not only have you increased your earning potential, you now have the opportunity to utilise positive social dynamics and peer learning.

Structured exercise progressions provide a framework for better program design and athlete development, improved coach and athlete performance, and provide direction in a constantly changing environment. By building exercises as we build clients, we are able to consistently target the right balance between challenge and success, while keeping us nimble enough to respond to the unpredictable environment we often operate in. Ultimately, it aims to increase our coaching effectiveness so that the our athletes can reach their potential.

References

- Brewer, C. Athletic Movement Skills – Training for Sports Performance. Human Kinetics, Sydney, Australia. 2017.

- Zaichowsky, L, Peterson, D. The Playmaker’s Advantage – How to Raise Your Mental Game to the Next Level. Gallery Books, New York, USA. 2018.

Subscribe to our blog

Subscribe to receive the latest blog posts to your inbox every week.

Related posts

It is Time to Change Up Your Programming