From the GA's Desk: The Scientific Approach to Training

Author Lorenzo Pelloni is a Graduate Assistant Sport Performance Coach at Springfield College.

Lorenzo Pelloni - “Building solid and lasting relationship with your athletes”

The "art" of coaching and the main characteristics that differentiate good coaches that can build genuine and impactful relationships with athletes have been studied scientifically. The main goals of those studies were to understand the behaviors, emotions, and knowledge that can impact the coach-athlete relationship to achieve the desired common results.

Coaching has been defined as a process of social interaction (1). Considering our field, sometimes strength and conditioning coaches might argue with this definition, emphasizing more the technical aspects of the role, such as biomechanics and physiology, but we should not forget that our athletes are people before being actual athletes. We should be training them like athletes and treating them as people we care about.

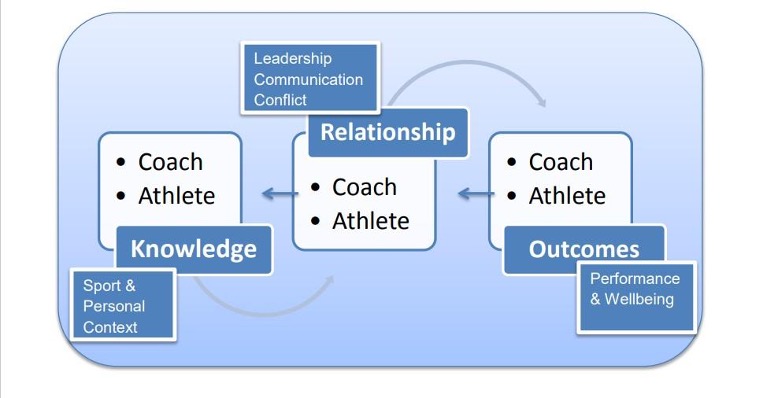

Moreover, the coach-athlete relationship is not unidirectional, with the coach only leading the process. It is dyadic; both the athlete and the coach influence it (Figure 1), and a 3 C's+1 has been proposed to define this dyad (3).

Figure 1: A system of coaching effectiveness that incorporate the collaboration of both parts, coach and athlete.

The 3 C's + 1 model takes into account: Closeness (trust, like respect, appreciation), Commitment (desire to maintain a relationship over time), Complementarity (cooperation and effectiveness), and Co-orientation (how reciprocal the coach and athlete perceptions of the relationship are). This model has been utilized to understand how the strength and conditioning coach is perceived by high-performance athletes (2). The results collected by athletes' answers reported how closeness, including trust, liking, respect, and sense of humor, are important characteristics of coaches' personalities that affirm the coach-athlete relationship. This data highlights how the interpersonal skills in high-level athletes’ perception of S&C coaches are considered predominant compared to the knowledge and technical skills. Nonetheless, noted that a high level of interpersonal skills helps build a positive relationship with athletes; it has also been reported that credibility and results of the program are factors that positively influence it, highlighting the importance of professional skill as well. I think we should take a holistic approach and maximize both of those skills, inter-intrapersonal and professional, when designing and administering a program.

Real Life Coaching

But after this scientific overview, let's talk more about how we can and should behave in the real world to get the most out of our relationship with our athletes, both from a performance and personal standpoint. First, I believe there is a reason why our job is "Strength and Conditioning coaches'' and not "Strength and Conditioning administrators," and we should understand how impactful our job can be. Our duty as coaches goes far beyond the simple program administration; we have the privilege and power to impact our athletes and impact them long-term. For this reason, we should not limit our job only to prescribing numbers and exercises to our athletes.

Knowledge or Communication? How About Both?

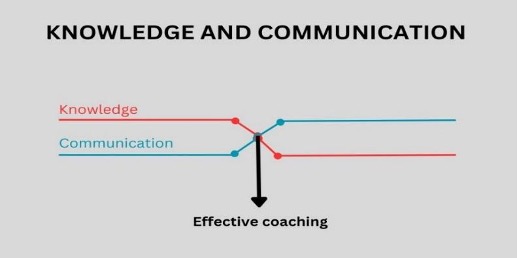

Knowledge does not occupy a secondary role in our job but should be utilized alongside our intra- and interpersonal skills. A quote perfectly defines this concept: "They don't care how much you know until they know how much you care." This phrase represents an undervalued aspect of interacting with teams and athletes. The knowledge that resides inside the coach's mind is essential, but a successful program depends not only on design but execution. Let's try to go deeper with an example to better understand the differences between utilizing interpersonal skills and not only technical ones in coaching. One coach with a "perfect" plan on paper in a physiological sense but who delivers the program poorly and a coach with an average plan on paper who coaches exceptionally well and can engage the athletes. Who is going to have better results? Both might have a place in the coaching process. Still, we often forget that coaching behaviors, more than physiological and biomechanical implementations, can have a greater overall outcome of a training program and impact the work.

On the other hand, we do not need only interpersonal skills to build a relationship with our athletes and make them succeed. Teaching skills, such as communication, planning, and technical knowledge, are essential foundations of the coach-athlete relationship. It would be wrong to suggest that "simply" by demonstrating good coaching behaviors, we can achieve positive outcomes. "You don't go to a doctor for their ability to communicate well. We want their technical expertise, such as diagnosis and treatments". The ultimate goal should be to see these skills as parallel lines, that once there is the need for coaching, they converge into a common point and do not diverge on different paths.

Defining Your Values

Ask yourself; what are the values that allow us to build a lasting and successful relationship with our athletes?

My personal values, for now, that I consider staple for building a positive and lasting relationship are: trust, sense of humor, knowledge, and care.

Trust

Trust is the willingness to be open and vulnerable with someone else. Establishing trust in a relationship might take a long time, especially when you see your athletes twice a week for one hour. We must prove ourselves as coaches to demonstrate credibility and integrity over weeks. Some ways that have been found useful to help build trust are positive feedback and listening and speaking to the athlete, even about life outside training (with boundaries, especially at collegiate-level). Trust is at the foundation of a healthy and successful relationship, and I believe that without trust, there can’t be respect. Consequently, a relationship can’t exist where both parties work for a common and pre-established goal.

Sense of Humor

As a coach with sense of humor (I think), I believe this trait doesn’t have to be hidden, of course, with boundaries and professionalism taken into account. But, as coaches, I think we often tend to take ourselves too seriously from this standpoint, and we should ask ourselves how we would feel if our athletes would make us laugh and create a better environment where we enjoy working. We all know what the answer would be. So, why don’t we start implementing this behavior? Especially in a situation where the sport might have more importance than the weight room, we should be able to make the environment enjoyable for our athletes and turn it from a place where they have to go into a place they WANT to go.

A good sense of humor is vital. If you can develop the skill to make anyone laugh, it is a highly valued skill, and it will help you in the process of building trust with the athletes.

Knowledge

As mentioned before, technical skills occupy a big role in our job as strength coaches. Being credible through a designed and personalized program help build trust and strengthen the relationship with our athletes. If strong relationship and good program administration (periodization, exercise selection) work together, we are likely to achieve the ultimate goal.

Care

Ultimately, it all comes down to knowing the person we are relating with. Everyone is unique and has specific and different traits/behaviors. As strength coaches, we are used to studying the sport and making a good and detailed needs analysis that will further help us plan our program. We should consider that in understanding who our athletes are, beyond being the team's middle blockers or goalie, we should probably run a "personal needs analysis" of the people we communicate with, as we do for the sport. Better understanding the preferences and traits of our athletes will allow us to get the most out of them, and our approaches will help the athlete achieve the outcome faster. Sometimes, as well as asking ourselves what the energy system or the primary injuries of the sport is, we should ask ourselves what the personality of our athletes (introvert, extrovert), which type of coaching/energy they have enjoyed the most, and get value from, etc.

When coaching, the perfect recipe does not exist. But, as with everything in life, with trials and errors, discussions with other coaches, and reading and listening to coaching resources, we can better understand and be aware of what might lead to increasing our chances of building positive and lasting relationships with our athletes.

Combining this awareness and a more scientific understanding of what athletes look for in an S&C coach will improve our coaching behaviors and perhaps turn a good relationship into a better and more lasting one.

References

- Côté, J., & Gilbert, W. (2009). An integrative definition of coaching effectiveness and expertise. International journal of sports science & coaching, 4(3), 307-323.

- Foulds, S. J., Hoffmann, S. M., Hinck, K., & Carson, F. (2019). The coach athlete relationship in strength and conditioning: High performance athletes’ perceptions. Sports, 7(12), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7120244

- Jowett, S. (2007). Interdependence Analysis and the 3+1Cs in the Coach-Athlete Relationship. In S. Jowette & D. Lavallee (Eds.), Social Psychology in Sport(pp. 15–27). Human Kinetics

Subscribe to our blog

Subscribe to receive the latest blog posts to your inbox every week.

Related posts

7 Things to Consider Before Building a Sport Science Program

My Beef with Evidence-Based Practice